Marching Order

Marching Order is a sequence of repeating forms organized consecutively, one after another, that establish a measured spatial order. more

Marching Order | School K-12

application

In schools K-12 Marching Order is frequently used to give organizational structure to libraries, lunchrooms and classrooms.

research

Marching Order seeks to control the school environment by giving order to large spaces and structure to smaller spaces. Similar to its use in workplaces, Marching Order in schools "organizes the placement of interior furnishings, such as desks and file cabinets... emphasizing the regularity of the arrangement and communicating strong messages of how one should circulate throughout and interact with the space."1 In schools, the regulation and treatment of space is key, maintaining organization over both space and students.

History & Theory

It is impossible to discern when Marching Order began to be used in schools; after all, "geometric order is a basic human need desired in any planned situation- people instinctively try for such order in furniture arrangement in their homes and expect to find it in offices . . . The human inclination to build on grid-iron plans with rectilinear box forms is actually more a matter of convenience to draftsman, surveyor and builder than the result of any real thought or philosophy."2 That said, there have been changes in school planning theory.

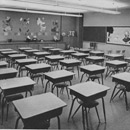

William Caudill of the famed school design firm, Caudill Rowlett Scott (CRS), writing about the needs of schools in 1951, speaks of the way schools were prior to that time period. "Many years ago classroom space had no need for versatility . . . it had only one job to do, to surround the five rows of fixed desks- and that is about all except possibly to provide some space at the front of the room so that the pupil or teacher could stand by a blackboard." Marching Order was the traditional classroom format, the rows of desks that Caudill references, long before 1950. Although 1950 was a period of reawakening for school design, Marching Order is still used consistently in school buildings.3

When analyzing various classrooms layouts, Caudill has this to say about "the conventional formal seating arrangement: although [it] is associated with old time teaching methods, there are occasions suited to this, [five rows of fixed desks], arrangement in up-to-date programs. It is good for tests, writing drills, and so on."4 Caudill's statement is still accurate; Marching Order continues to be used to this day, but not just for the reasons he lists here; the effect Marching Order has on its environment spans beyond just a good arrangement for tests.

In the 1960's, though Marching Order continued to be used, rigid classrooms faded from popularity. "Open plan" classrooms and schools were created. These new schools had fewer interior walls and reconfigurable, flexible environments. They have been identified as being "an arrangement more conducive to student needs," allowing a wider range of seating patterns than a traditional classroom.5

Further analysis of Marching Order reveals the theory behind its use. According to architect and author Francis D.K. Ching, "the organizing power of the grid results from the regularity and continuity of its pattern that pervades the elements its organizes... its pattern establishes a stable set or field of reference points and lines in space with which the spaces of a grid organization, although dissimilar in size, form, or function, can share a common relationship."6 Marching Order is used to visually organize space, allowing for a greater depth of spatial understanding and perception.

Godfrey Thompson's book on library planning and design echoes the insight of Ching and Pile, stating that in libraries, "the aim is to house as many books as possible in conditions convenient to both staff and readers.... it was suggested... that the architect should choose a structural grid which can relate to the module most vital to his client's interest, and that this is the unit of shelving."7 As in libraries, the grid used in schools provides access and organization for the student, enabling him or her to find their way with greater ease.

Beyond just its organizational qualities, Marching Order serves a beatific purpose as well. The organizational line or grid of identical forms separated by equal intervals creates rhythm. "Architectural rhythm [is] expressed by successive solids and voids . . . [this too is an] important [factor which goes] to make architecture out of mere shelter." Ching echoes Caudill's sentiment, stating that, "the movement may be of our eyes as we follow recurring elements in a composition, or of our bodies as we advance through a sequence of spaces... in either case, rhythm incorporates the fundamental notion of repetition as a device to organize forms and spaces in architecture."8

Effect

Beyond the "basic human need [for geometric order] in planned situations," there exists some additional research pertaining to schools, as to why Marching Order is needed. According to a study in Schools for the Future, "children want varied but not chaotic schools with unconstrained building forms, including non-oppressive ceilings and appealing color schemes." Marching Order keeps schools from becoming chaotic; it establishes, rhythm, order, and organization, thus making the school more appealing both architecturally and to its inhabitants.9

Organizing a school using Marching Order also facilitates wayfinding in schools. Kevin Lynch's book, The Image of the City discusses the way that people navigate, creating mental maps and using visual markers such as landmarks, such as Showcase Stair,10 nodes, paths, and districts to figure out their locations. Furniture arranged in rows and with columns may be identified by students as a spatial district. According to Lynch, "districts are the medium-to-large sections of the city, conceived of as having two-dimensional extent, which the observer mentally enters ‘inside of,' and which are recognizable as having some common, identifying character... always identifiable from the inside, they are also used for exterior reference if visible from the outside."11 By identifying these districts, paths and landmarks are more easily distinguished, allowing students to find their way more easily within the school building.

According to Tanner and Lackney, traditional arrangements such as Marching Order reflect "limited space and density issues;" unfortunately, arranging students in Marching Order can involve too much stimulation, lack of privacy, interruptions, and disciplinary problems. While open classrooms may be "more conducive to student needs... research indicates [that] traditional classroom [Marching Order] students outperform open classroom students in academics."12

Chronological Sequence

Marching Order is an instinctual human response to the built environment. As such, it has been used in schools virtually since their inception, making its origin difficult to trace. As such, it makes sense to trace the history of its use in the modern school building. According to William Caudill, "1950 represents a year in history when for the first time a large majority of architects and educators throughout the entire nation got together to try to solve their common problems . . . the professional journals began to be more discreet in their choice of schools for publication . . . by 1950, the battle between contemporary and traditional was won." Therefore, it makes sense to begin the chronology of Marching Order in the modern school building in 1950.

The first example of Marching Order occurs in 1954 at the Frederick Douglass Stubbs School in Wilmington, Delaware. The school was built to accommodate 800 students. Among the interior finishes used are "plywood, plaster, ceramic tile, [and] asphalt tile." An image of the school shows the cafeteria, wherein five rows of three tables are lined up in rows. On the ceiling, there are three strips of lights in addition to two series of skylights, which lie in parallel lines against the wall. Against the far wall, there are a series of glass windows that look out onto the hallway. The light from these windows illuminates a lower hall.13

Another example of Marching Order comes from the Mattie Lively Elementary School in Statesboro, Georgia in 1955. The school was built for the low cost of $207,823 and is 23,954 square feet in size. Like the previous example, Marching Order is found in the school's cafeteria, where tables are arrayed in a grid of four columns by three rows. Around the tables are evenly spaced metal folding chairs. The room also acts as an auditorium, hence at the far end of the image is a large, upraised stage. against the adjacent wall are large windows, leading from railing height up to the ceiling.14

Winner of a First Honor Award for school design in the Gulf States in 1956, the Horace Mann School of Little Rock, Arkansas has a wedge-shaped plan that created a series of courtyards onto which classrooms looked out. One such classroom contains a large number of desks arrayed in a grid. These desks face a large chalkboard that runs along the front wall of the space. A series of beams march across the ceiling plane and reach out past the window plane to support the roofline. Windows line the wall adjacent to the chalkboard, from railing height to the ceiling. Several light fixtures are also seen in the ceiling plane, arranged in a grid of two by three.15

Another school planned around a series of courtyards, Union High School was built in 1958 in Lodi, California. "The organization of the plan, say the architects, was based on ‘mass movements' within the school." An image from the school depicts the cafeteria, which looks out onto the main courtyard. Upward of seven rows of tables are pictured, with multiple tables composing each row and numerous chairs placed on opposite sides of the tables. Along the far wall of the cafeteria are windows that come to about nine feet in height and look out onto the rest of the school. Rhythm is created in the space through the use of beams in the ceiling and the windows' mullions.16

In Bloomfield Hills, Minnesota, the Bloomfield Hills Junior High School was built in 1959. It features "bright, highly pleasant indoor and outdoor teaching areas [that] avoid monotony." One of the school's classrooms features desks that are arrayed in a Marching Order grid; all are spaced evenly apart to create aisles in between columns and rows. The desks are spread the width of the classroom. Due to the placement of classrooms in plan in a "checkerboard fashion," the classroom has windows on at least two sides, possibly three sides, with one wall having chalkboards below a string of windows. Fluorescent lights run parallel to one another across the ceiling plane. Each desk has its own, removable chair that fits neatly under the desk.17

The Robert E. Lee Senior High School in Tyler, Texas, "reflects the wide open character of Texas ... spreading out over a large area of the site." Meant for a large number of students, the school's gym seats more than 2000. This is reflected in the size of the cafeteria, which features more than seven long rows of tables. Large floor-to-ceiling windows take up one wall of the space, from which the rows of tables are aligned. There is some variation in the ceiling plane; part of it drops lower to, seemingly, create a zone above the tables. In this, canned lights are set in a diagonal pattern, at an angle to the seating below. The photo described features only "the enclosed portion of the cafeteria."18

Marching Order is used in the library of the Smithtown Central High School, built in 1960 in Smithtown, New York. Adjoining the commons room, the library has a high ceiling and windows on at least two sides, with many reaching from floor to ceiling. Rectangular tables, seating four chairs each are arrayed in a grid down the length of the room. Large fixtures hang from the ceiling, in addition to cans that run parallel to the room. Bookshelves are located on the walls of the space.19

Not only did the J.S. Clark Junior High School feature Marching Order in the arrangement of its library's tables, it also features them in the book stacks as well. The school, built in 1960 in Shreveport, Louisiana serves 1500 students and houses grades seven through nine. The library is large, with windows reaching from railing-height up to the ceiling and columns punctuating the space, ending with large, circular columns. The grid of rectangular wooden tables, which appear to seat four each, run perpendicular to the line of bookshelves. Lights in the ceiling run parallel to the shelves as well.20

In Euless, Texas, the Midway Park Elementary School, built in 1967, featured Marching Order in the arrangement of the desks in its classrooms. The school was, at its inception, "the first completely round building with classrooms trapezoidal in shape." In its classrooms, the desks are considered mobile, easily moved into a variety of arrangements. Pictures from the classrooms show a room with desks arrayed in a grid, with hanging fluorescent lighting running perpendicular to the columns of desks. There are chalkboards at both the front of the room and the sides, with tackable space in back and built-in storage closets along the other side of the wall.21

Low Heywood School, built in Stamford, Connecticut, stands as an example of the new ideas in school planning recorded by the firms Perkins & Will and SMS Architects in 1970. Despite the new directions that schools were heading in, they still incorporated Marching Order into their plans. An image of such a school features a classroom adjacent to a hallway. The ceiling of the hall is lowered, providing some delineation between the two spaces. In the classroom area, the desks are arrayed neatly in a grid. Doors at the back of the classroom space appear to lead to a library. While the school has a more free-flowing plan, Marching Order continued to be used to order space.22

In 1975, the Burlington Senior High School was built in Burlington, Massachusetts. Its innovative plan called for "open and closed plan spaces [to allow] a variety of teaching opportunities." The large school utilizes Marching Order in its library, which is "three levels high... [and is] designed as a high and dramatic space as an economical and practical way to give the library identity, or a sense of place". Images from the library show a large open room with skylights covering the ceiling and a monolithic, multi-story stair descending into it. Visible on the first floor, adjacent to the open space and separated by columns, are a series of bookshelves in Marching Order. A series of desks are visible in front of the columns, also set up in Marching Order. Study carrels are also shown in the foreground of the image.23

Fremont High School of East Oakland, California was built in 1980 and designed for a population of 1500 students, though in reality, it services over 1800. The school's cafeteria are centrally located and contain a series of tables arrayed in Marching Order with six chairs pushed up to each table. The space is punctuated by a series of columns that correspond to the ceiling height of the space, which goes from a standard height near the food service area to half a story higher in the eating area. There, hanging fluorescent lights run parallel to the tables.24

Designed by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates, the Westover School in Middlebury, Connecticut, built in 1985, made use of Marching Order in its library space. The new space includes a "soon-to-be-necessary new library" and "the transformation of an existing infirmary into the needed science facility." The multi-level library features a series of bookshelves in Marching Order, adjacent to large floor-to-ceiling windows that overlook the nearby fields. Looking down on this space are a series of square tables and low bookshelves. Above this, a series of three large circular skylights overlook the tables. The space features white walls and wood trim in a clean, modern design.25

Another photograph from the Westover school shows one of the new science classrooms. Here, the chairs have small writing surfaces attached to them, allowing for greater flexibility. Despite the change in furniture, the desks are arrayed in a Marching Order grid. A clerestory window in the back of the space brings in light from an adjacent lab. Cabinets line the wall below, with plenty of counter space. Near the window on the adjacent side are two long counters with built in sinks and built-in outlets, ready for experiments. A similar instructor's counter sits at the front of the room. Lights in the ceiling are arranged in lines, perpendicular to the counters on the adjacent wall.26

In Lawrence, Massachusetts, Arlington Elementary School, built in 1988, architect Earl Flansburgh has designed a school that was the "result of carefully studied massing, detailing, colors, and textures." At the juncture of the school's wings for older children and younger children is a library. Like many of the other libraries, this one also utilizes Marching Order in the alignment of its bookshelves, which are set in rows in the center space of the room. A second floor looks down from above, accessible from a large stair to the far left. Beams in the ceiling run parallel to the shelves and skylights running along the front wall let in natural light.27

Built in 1991 in Hope, Indiana, Hope Elementary School fulfilled administrators' wishes for "a one-story structure that [is] economical but at the same time eye-catching," as well as teachers' desire for "classrooms with lots of windows, lots of chalkboard space, and lots of storage." One such classroom contains desks arrayed in a Marching Order grid, facing a chalkboard at the front of the room. Fluorescent lights are also arrayed in parallel rows in the ceiling plane, illuminating the space. The classroom can be seen from a window linking the space to the adjacent hallway.28

Troy High School, designed by Perkins & Will for the community of Troy, Michigan in 1993. The school follows the trend "toward creating educational parks on larger sites and using the facilities as cultural and recreational centers." Marching Order was used in the school's cafeteria, which is "south and east-facing [and] has larger [windows than the classrooms]". An image of the space shows white walls and ceiling, with a series of columns lining a circulation path to the left. The blocks that compose the wall surfaces give texture to the space. To the right, long tables stand in Marching Order, surrounded by mobile stools.29

A 1997 renovation of the Lick-Wilmerding School includes "a new library [as the] top priority on the school's long list of physical needs." The school, located in San Francisco, California, hoped that the library would keep in mind their motto of "head, heart, and hands" and believed that the architects' decision to "expose the structural elements at the library's vaulted roof and cement-panel fasteners, [and] choice of materials, such as Italian artisan plaster and stained concrete, which evidence technique and weathering" fit with that concept. The library's many stacks are arrayed in Marching Order, with circulation paths to the left side and down the middle of the two columns of shelves. Changes in the floor's coloring also denote circulation paths. Large windows abut the other side of the space. Fluorescent lights are hung in a Marching Order grid from the ceiling, perpendicular to the shelves.30

Site visits confirmed the existence of Marching Order outside of trade magazines. The library of the Flit Hill School in Oakton, Virginia, built in 2001, features square tables arrayed in a Marching Order grid in its library. On top of desks are placed two lamps to provide adequate lighting. A balcony space overlooks the library with stacks, also in Marching Order, arrayed on the far side of the room.31

Evidence of Marching Order was also found in the classrooms of Cumberland Valley High School in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, renovated by Liberty Engineering in 2003. Here, desks are arrayed in even rows in the classroom, facing a large chalkboard at the front of the room. These rows fill the room to capacity, leaving only space in front of the chalkboard and on one side for circulation.32

"The first independent school in Manhattan to build a new facility in decades," the Lycée Français in New York City maximizes space through the use of stacking and skylights. The school's "commons, a large room vital to maintaining community" are illuminated by skylights and, in addition, are "bordered by a two-story glass curtain wall" which allows the courtyard above the commons to appear as though it is "floating" in the center of the school. Inside the commons itself, tables are arranged in a Marching Order grid, with eight chairs placed at each collapsible table. Walls of the school are white, with accents provided by metal and colored furniture in more subdued hues.33

In 2005, Perkins & Will designed the new Roger Ludlowe Middle School for the town of Fairfield, Connecticut. Among the features of the new building are "simple, airy classrooms [that] collect reflected light, thanks to 11-foot, floor-to-ceiling windows and exterior cedar fins that function as bries-soleils." An image of one such classroom features desks and chairs arrayed in a familiar grid pattern. On the far side of the classroom, a window overlooks the rest of the school and a courtyard. In the corner of the room sits a teacher's desk and above it, a television hangs from the ceiling. The walls, floor, and ceiling are all a neutral color. At the front of the room, the desks face a large white board and its adjacent tackable surfaces.34

St. Matthew's Parish School, renovated in 2009 in Pacific Palisades California, was designed to accommodate "325 students from prekindergarten through eight grade." Among the additions made is a 9,850-square-foot library, which became "a magnet on campus, [and] addresses all of the children, with a storytelling nook, stacks, and worktables". The library has a wood-paneled roof, from which a series of large light fixtures hang down into the atrium space. To the left of the stair, the ceiling is lowered to one story; here, there are a series of bookshelves arrayed in Marching Order with hanging fluorescent lights in parallel above. Windows look out to the left and to the far wall of the space.35

In North Hollywood, California, the Roy Romer Middle School was built to consolidate sixth through eighth graders that had formerly attended several separate schools. The school's library utilizes Marching Order in the arrangement of its stacks, which have "long views out across the fields . . . [while the windows] facing the schoolyard evoke openness and transparency". Adjacent to the windows, the stacks are lined up parallel to the grid of fluorescent lights above them. Wood beams lie perpendicular across the space. In the central space, a large counter with a wall behind it serves as a librarian's desk; in front, two six-person tables are lined up next to one another.36

Marching Order is a natural solution to interior design, which has been to a greater degree supported by research into educational environments. It continues to be used frequently in schools, demonstrated here from 1950 to the present, making it a widely accepted and relevant practice in the field of architecture and education.37

end notes

- 1) Shuqing Yin, "Theory Studies: Workplace," (M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2011), 70; http://www.intypes.cornell.edu/intypesub.cfm?inTypeID=95 (accessed Jul. 11, 2012). Marching Order has also been identified as an archetypical practice in retail and showroom design.

- 2) John Pile, Interiors: Second Book of Offices (New York: Whitney Library of Design, 1969), 261.

- 3) William W. Caudill, Toward Better School Design (Ann Arbor, Mich.: FW Dodge Corp, 1954), 13-14.

- 4) Caudill, Toward Better School Design, 141.

- 5) C. Kenneth Tanner and Jeffrey Lackney, Educational Facilities Planning (Boston: Pearson Education, Inc., 2006), 93.

- 6) Francis D.K. Ching, Architecture, Form, Space & Order, Second Edition, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1996), 230.

- 7) Godfrey Thompson, Planning and Design of Library Buildings, 3rd Ed., (London: Butterworth & Co. (Publishers) Ltd, 1989), 139.

- 8) Caudill, Toward Better School Design, 141; Ching, Architecture, Form, Space & Order, 230.

- 9) Pile, Interiors: Second Book of Offices, 261; Rotraut Walden, Schools for the Future: Design Proposals from Architectural Psychology (Germany: Hogrefe and Huber Publishers, 2009), 82.

- 10) A Showcase Stair is an extravagantly designed architectural feature in which the stair itself becomes a prominent display element. Its functionality is often secondary to the spatial drama created by the stair's structure, form, materials and lighting. It has been identified in Apartment, Hotel, House, Retail and School design. Katherine Mooney, "Theory Studies: Archetypical Practices in American 1-12 School Design," (M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2011).

- 11) Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City (Boston: MIT Press, 1960), 47.

- 12) Tanner and Lackney, Educational Facilities Planning, 93, 403.

- 13) Fredrick Douglass Stubbs School [1954] Victorian & Samuel Homsey, architect; Wilmington, DE in "Delaware School Profits by Adjoining Park," Architectural Record 116, no. 2 (Aug. 1957): 165-68; PhotoCrd: Joseph W. Molitor.

- 14) Mattie Lively Elementary School [1955] Aeck Associates, architect; Statesboro, GA in "Two Similar Elementary Schools in Rural Georgia," Architectural Record 117, no. 2 (Feb. 1955): 198-200; PhotoCrd: Joseph W. Molitor.

- 15) Horace Mann High School [1956] Erhart, Eichenbaum, Ranch, and Blass, architect; Little Rock, AK in "Courtyards Integrate Low-budget School," Architectural Record 122, no. 4 (Oct. 1957): 189-94; PhotoCrd: Earl Saunders.

- 16) Union High School [1958] Falk & Booth, architect; Lodi, CA in "Courts Give Abundantly Varied Outdoor Space," Architectural Record 123, no. 2 (May 1958): 216-19; PhotoCrd: Roger Sturtevant.

- 17) Bloomfield Hills Junior High School [1959] Linn Smith Associates, Inc., architect; Bloomfield Hills, MI in "Roof Shapes Highlight Flexible School," Architectural Record 126, no. 2 (Aug. 1959): 162-64; PhotoCrd: Lens Art.

- 18) Robert E. Lee Senior High School [1960] Caudill, Rowlett & Scott, architect; Tyler, TX in "Large School Accents Outdoor Learning," Architectural Record 127, no. 5 (May 1960): 206-09; PhotoCrd: Jay Oistad & Assoc. photos.

- 19) Smithtown Central High School [1960] Ketchum & Sharp, architect; Smithtown, NY in "Two High Schools Share Activity Areas," Architectural Record 127, no. 5 (May 1960): 209-11; PhotoCrd: G. Amiaga photos.

- 20) J.S. Clark Junior High School [1960] William B. Wiener, Morgan & O'Neal, architect; Shreveport, LA in "Schools," Architectural Record 128, no. 2 (Aug. 1960): 194-95; PhotoCrd: Film Arbor Studio.

- 21) Midway Park Elementary School [1967] Woodward & Associates, architect; Euless, TX in "School in the Round," Interior Design 36, no. 12 (Dec. 1967): 110-15; PhotoCrd: Anonymous.

- 22) Low Heywood School [1970] SMS, architects; Stamford, CT in "New Directions in School Planning," Architectural Record 148, no. 5 (Nov. 1970): 121-34; PhotoCrd: Ezra Stoller Photos.

- 23) Burlington Senior High School [1975] Architects Design Group, Inc., architect; Burlington, MA in "More for Less," Architectural Record 158, no. 6 (Dec. 1975): 90-91; PhotoCrd: Steve Rosenthal.

- 24) Fremont High School [1980] Charles Davis of Esherick, Homsey, Dodge, and Davis, architect; East Oakland, CA in "Four Schools with Thought," Architectural Record 168, no. 2 (Aug. 1980): 109-13; PhotoCrd: Peter Aaron, ESTO Photographics, Inc.

- 25) Westover School [1985] Gwathmey Siegel & Associates, architect; Middlebury, CT in "A Lesson in Deportment," Architectural Record 173, no. 2 (Feb. 1985): 124-33; PhotoCrd: Timothy Hursley/The Arkansas Office.

- 26) Westover School [1985] Gwathmey Siegel & Associates, architect; Middlebury, CT in "A Lesson in Deportment," Architectural Record 173, no. 2 (Feb. 1985): 124-33; PhotoCrd: Timothy Hursley/The Arkansas Office.

- 27) Arlington Elementary School [1988] Earl R. Flansburgh Associates, Inc., architect; Lawrence, MA in "Varied Textures and Subtle Color Enrich a Conservative Pattern," Architectural Record 176, no. 10 (Sep. 1988): 112-13, PhotoCrd: Sam Sweezy Photos.

- 28) Hope Elementary School [1991] Taft Architects, architect; Hope, IN in "Hearing the Community," Architectural Record 179, no. 1 (Jan. 1991): 102-05; PhotoCrd: Paul Warchol Photos.

- 29) Troy High School [1993] Perkins & Will, architect; Troy, MI in "School Sprit," Architectural Record 181, no. 8 (Aug. 1993): 96-103; PhotoCrd: Balthazar Korab Photography.

- 30) Lick-Wilmerding School [1997] Simon Martin-Vegue Finkelstein Moris, architect; San Francisco, CA in "Schools," Architectural Record 185, no. 10 (Oct. 1997): 102-05; PhotoCrd: Tim Griffith.

- 31) The Flint Hill School [2001] Chatelain Architects; Oakton, VA; SIte Visit, Katherine Mooney, 13 August, 2012.

- 32) Cumberland Valley High School [2003] Liberty Engineering, Project Architects; Mechanicsburg, PA; Site Visit, Katherine Mooney, Aug. 13, 2012.

- 33) Lycée Français [2004] Polshek Partnership Architects, architect; New York City in "Environment Counts," Architectural Record 192, no. 3 (Mar. 2004): 131-34; PhotoCrd: Richard Barnes.

- 34) Roger Ludlowe Middle School [2005] Perkins Eastman, architect; Fairfield, CT in "Back to the Future," Architectural Record 193, no. 12 (Dec. 2005): 148-51; PhotoCrd: Woodruff/Brown.

- 35) St. Matthew's Parish School [2009] Lake/Flato Architects and Gensler, architect; Pacific Palisades, CA in "Building on the Past," Architectural Record 197, no. 7 (Jul. 2009): 87-91; PhotoCrd: Benny Chan.

- 36) Roy Romer Middle School [2010] Johnson Fain-Scott Johnson, architect; North Hollywood, CA in "Schools of the 21st Century," Architectural Record 198, no. 1 (Jan. 2010): 93-97; PhotoCrd: Fotoworks/Benny Chan.

- 37) Evidence for the archetypical use and the chronological sequence of Marching Order in 1-12 schools was developed from the following sources: 1950 Fredrick Douglass Stubbs School [1954] Victorian & Samuel Homsey, architect; Wilmington, DE in "Delaware School Profits by Adjoining Park," Architectural Record 116, no. 2 (Aug. 1957): 168; PhotoCrd: Joseph W. Molitor.; Mattie Lively Elementary School [1955] Aeck Associates, architect; Statesboro, GA in "Two Similar Elementary Schools in Rural Georgia," Architectural Record 117, no. 2 (Feb. 1955): 199; PhotoCrd: Joseph W. Molitor.; Horace Mann High School [1956] Erhart, Eichenbaum, Ranch, and Blass, architect; Little Rock, AK in "Courtyards Integrate Low-budget School," Architectural Record 122, no. 4 (Oct. 1957): 191; PhotoCrd: Earl Saunders.; Union High School [1958] Falk & Booth, architect; Lodi, CA in "Courts Give Abundantly Varied Outdoor Space," Architectural Record 123, no. 2 (May 1958): 219; PhotoCrd: Roger Sturtevant.; Bloomfield Hills Junior High School [1959] Linn Smith Associates, Inc., architect; Bloomfield Hills, MI in "Roof Shapes Highlight Flexible School," Architectural Record 126, no. 2 (Aug. 1959): 163; PhotoCrd: Lens Art.; 1960 Robert E. Lee Senior High School [1960] Caudill, Rowlett & Scott, architect; Tyler, TX in "Large School Accents Outdoor Learning," Architectural Record 127, no. 5 (May 1960): 209; PhotoCrd: Jay Oistad & Assoc. photos.; Smithtown Central High School [1960] Ketchum & Sharp, architect; Smithtown, NY in "Two High Schools Share Activity Areas," Architectural Record 127, no. 5 (May 1960): 211; PhotoCrd: G. Amiaga photos.; J.S. Clark Junior High School [1960] William B. Wiener, Morgan & O'Neal, architect; Shreveport, LA in "Schools," Architectural Record 128, no. 2 (Aug 1960): 195; PhotoCrd: Film Arbor Studio.; Midway Park Elementary School [1967] Woodward & Associates, architect; Euless, TX in "School in the Round," Interior Design 36, no. 12 (Dec. 1967): 110; PhotoCrd: Anonymous.; Midway Park Elementary School [1967] Woodward & Associates, architect; Euless, TX in "School in the Round," Interior Design 36, no. 12 (Dec. 1967): 111; PhotoCrd: Anonymous. 1970 Low Heywood School [1970] SMS, architect; Stamford, CT in "New Directions in School Planning," Architectural Record 148, no. 5 (Nov. 1970): 132; PhotoCrd: Ezra Stoller Photos.; Burlington Senior High School [1975] Architects Design Group, Inc, architect; Burlington, MA in "More for Less," Architectural Record 158, no. 6 (Dec. 1975): 91; PhotoCrd: Steve Rosenthal photos.; 1980 Fremont High School [1980] Charles Davis of Esherick, Homsey, Dodge, and Davis, architect; East Oakland, CA in "Four Schools with Thought," Architectural Record 168, no. 2 (Aug. 1980): 113; PhotoCrd: Peter Aaron, ESTO Phographics, Inc.; Westover School [1985] Gwathmey Siegel & Associates, architect; Middlebury, CT in "A Lesson in Deportment," Architectural Record 173, no. 2 (Feb. 1985): 131; PhotoCrd: Timothy Hursley/The Arkansas Office photos.; Westover School [1985] Gwathmey Siegel & Associates, architect; Middlebury, CT in "A Lesson in Deportment," Architectural Record 173, no. 2 (Feb. 1985): 132; PhotoCrd: Timothy Hursley/The Arkansas Office photos.; Arlington Elementary School [1988] Earl R. Flansburgh Associates, Inc., architect; Lawrence, MA in "Varied Textures and Subtle Color Enrich a Conservative Pattern," Architectural Record 176, no. 10 (Sep. 1988): 112; PhotoCrd: Sam Sweezy Photos.; 1990 Hope Elementary School [1991] Taft Architects, architect; Hope, IN in "Hearing the Community," Architectural Record 179, no. 1 (Jan. 1991): 104; PhotoCrd: Paul Warchol Photos.; Troy High School [1993] Perkins & Will, architect; Troy, MI in "School Sprit," Architectural Record 181, no. 8 (Aug. 1993): 102; PhotoCrd: Balthazar Korab Photography.; Lick-Wilmerding School [1997] Simon Martin-Vegue Finkelstein Moris, architects; San Francisco, CA in "Schools," Architectural Record 185, no. 10 (Oct. 1997): 104; PhotoCrd: Tim Griffith.; Lick-Wilmerding School [1997] Simon Martin-Vegue Finkelstein Moris, architects; San Francisco, CA in "Schools," Architectural Record 185, no. 10 (Oct. 1997): 105; PhotoCrd: Tim Griffith.; 2000 The Flint Hill School [2001] Chatelain Architects; Oakton, VA; SIte Visit, Katherine Mooney, 13 August, 2012; PhotoCrd: Katherine Mooney, Intypes Project, 13 August, 2012.; Cumberland Valley High School [2003] Liberty Engineering, Project Architects; Mechanicsburg, PA; SIte Visit, Katherine Mooney, 13 August, 2012; PhotoCrd: Katherine Mooney, Intypes Project, 13 August, 2012.; Lycée Français [2004] Polshek Partnership Architects, architect; New York City in "Environment Counts," Architectural Record 192, no. 3 (Mar. 2004): 134; PhotoCrd: Richard Barnes.; Roger Ludlowe Middle School [2005] Perkins Eastman, architect; Fairfield, CT in "Back to the Future," Architectural Record 193, no. 12 (Dec. 2005): 151; PhotoCrd: Woodruff/Brown.; St. Matthew's Parish School [2009] Lake/Flato Architects and Gensler, architect; Pacific Palisades, CA in "Building on the Past," Architectural Record 197, no. 7 (Jul. 2009): 91; PhotoCrd: Benny Chan.; St. Matthew's Parish School [2009] Lake/Flato Architects and Gensler, architect; Pacific Palisades, CA in "Building on the Past," Architectural Record 197, no. 7 (Jul. 2009): 91; PhotoCrd: Benny Chan.; 2010 Roy Romer Middle School [2010] Johnson Fain-Scott Johnson, architect; North Hollywood, CA in "Schools of the 21st Century," Architectural Record 198, no. 1 (Jan. 2010): 97; PhotoCrd: Fotoworks/Benny Chan.

bibliographic citations

1) The Interior Archetypes Research and Teaching Project, Cornell University, www.intypes.cornell.edu (accessed month & date, year).

2) Mooney, Katherine Elizabeth. "Theory Studies: Archetypical Practices in American K-12 Schools." M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2012, 27-59.