Circle Round

Circle Round refers to the semi-circular grouping or shaping of furniture around a single focal point. Circle Round focuses attention on a specific, central source, blocking out visual distraction. more

Circle Round | School K-12

application

In K-12 school classrooms, Circle Round references the placement of furniture, typically desks and chairs, in a curved shape around a single focal point, typically a teacher, a chalkboard or projection screen, where instruction is occurs.

research

Circle Round facilitates a distraction-free environment, focusing the attention of the students on a single physical point. Instances of Circle Round typically occur in a classroom instruction environment, where desks are lightweight and easily manipulated into a variety of seating patterns. Circle Round is found more often in elementary than secondary environments, as younger children are more likely to be distracted and because the nature of instruction is more variable. It is also more frequently found in private schools or schools with few students per classroom, as the arrangement takes up more space than other desk arrangements such as Marching Order.1

Like Two by Two,2 Circle Round is frequently the result of the Intype Shuffle,3 the informal movement of lightweight furniture to accommodate various group sizes and spatial configurations.

History & Theory

The archetype Circle Round finds its origin in the ancient form of auditoriums, which may be traced back to the classical amphitheaters of ancient Greece and Rome. These amphitheaters, used primarily for entertainment, contained rows of curved, sometimes elevated, seating, focused around a central, circular orchestra. This traditional plan has been used not only in classical auditoriums and renaissance theater, but continues to inform the design of stages, opera halls, and cinemas as we know them today.

Ancient Greek amphitheaters were originally used to celebrate religious festivals honoring the god of wine, Dionysus. Most amphitheaters consisted of three parts; a stage, an orchestra, and finally, seating, in the from of concentric rows of benches.4 While the shape of the orchestra has evolved over time, it was originally a circle. From this, the rows of curved seating derive their shape.

While "the theatre at Athens... provided accommodation for no less than fourteen thousand persons... [and] is considered the prototype of all other [amphitheaters]," this sixth century theatre takes its shape from an even earlier form. "The smooth surfaced circular shape of the Greek orchestra has recently been explained [by] the form of the threshing floor... it is possible that gay dances at religious festivals and particularly at harvest time were performed in the same place where oxen had trodden out the grain or the grapes had been dried."5

Crowds of people would gather to watch these festival performances, annually honoring Dionysus. As Bieber states, "these people would celebrate the harvest by dancing in the same circle in which they threshed their grain. Over time, these festivals became grander, eventually evolving into the classical amphitheaters famous in Greek and Roman history. Often, these amphitheaters were just "a simple arrangement of benches set in the bowl of a hillside, with the slope built up artificially where the hill was insufficient."6 Some, like that at Athens, evolved from wooden benches to the stones that we see in ruins today.

Classical Greek and Roman drama saw a revival during the Italian Renaissance. Opulently wealthy Italian princes showcased these dramas in "temporary structures built within existing palaces... [later], permanent theaters were built [in] the mid-sixteenth century." These later theaters had their own, unique character, but were still patterned after the traditional amphitheaters. One of the earliest surviving examples of these Italian theaters is Andrea Palladio's Teatro Olympico (1580-1584) in Vincenza.7 This iconic building served as a precedent, not only for theaters, but for European opera houses as well; it remains one of the most iconic forms of theater today.

In describing the reiterations of auditoriums that have since been created, Forsyth speculated that "the criterion of visual intimacy generates a short, broad auditorium... for sightlines, the raked fan-shape is ideal."8 Circle Round is characterized, as Forsyth suggests, by a feeling of intimacy and closeness. In some circumstances, this closeness couples with the focus of the audience, creating an environment free of distraction.

Effect

In the classrooms of K-12 schools, Circle Round, as an educational and design strategy, creates a fan-shaped seating arrangement allowing children to focus visual attention on their instructor. While "open spaces [can be] divided by rolling equipment-storage cabinets, chalkboards, tackboards, [etc]," the use of Circle Round enacts the inherent benefits of the circle, "a centralized, introverted figure that is normally stable and self centering in its environment." Circles are particularly useful in large, open plans as "[placing] a circle in the center of a field reinforces its inherent centrality."9

Educational studies also show that "furniture and equipment should accommodate the arrangement of group work zones and discussion circles, not encumber these." Publications on open plan schools, schools that utilize "vast, wide-open areas... [grouped into] classroom clusters or pods," mention the importance of using "trapezoidal tables because they open more avenues of creative and functional arrangement." Such tables are shown later in this chapter.10

Chronological Sequence

In mid-20th century America, changes in architectural design coupled with a change in traditional views of education " . . . brought a new light to educational architecture, a new movement based on the needs of the pupil . . . it can certainly be said that 1950 represents a year in history when for the first time a large majority of architects and educators throughout the entire nation got together to try to solve their common problems."11 William W. Caudill, an architect, educator and author of twelve books in his field, including Space for Teaching and Toward Better School Design, led architects in research studies and collaborations with educators. According to Caudill, school design did not join the modernist architectural movement until around 1949, when suddenly, architects and interior designers reconsidered the rigid rows of seating used since the one room schoolhouse.

The collaboration between architects and educators, and the role of furniture manufacturers, resulted in the concept of an "open plan" (having no or few dividing walls between areas) in schools. To make use of the newly opened structure, as well as to accommodate ever-changing educational doctrines, architects created larger classrooms that could adapt to a wide variety of education curriculums. "Instead of regimented desks, [the modern classroom would have] chairs and tables light enough for children to move easily... the self-contained classroom is bigger than classrooms used to be, and different in shape. It opens to... become bigger and even more informal."12 Because chairs and tables were now easily moved, teachers could feel free to experiment with classroom layouts. The Intype Circle Round is a result of this experimentation.

In 1956 Architectural Record published the first example of Circle Round in a school setting, the Pocantico Hills Central School in Pocantico, New York. A photograph records the use of a classroom organization in which desks were arranged into a crescent-shaped row with a blackboard at the center. Each individual student had her or his own desk, allowing for a more precise curve to the circle. Although children are posed sitting in a Circle Round, they do not appear to be interacting with the space, but to be focused on the lesson. Instruction in this time period and for secondary school students such as these remained formal. Although Circle Round in the Pocantico Hills Central School signified a structured arrangement, it represented the beginning of a new era that moved furniture arrangement out of a grid. Just as importantly perhaps was the role the publication made in disseminating a new mode of arrangement to an audience of architects. It should also be noted that Perkins + Will was the architectural firm for the school, not Caudill's CRS (Caudill, Rowlett, Scott & Associates).13

By 1957, furniture manufacturers began to create furniture that reflected new educational practices. A photograph published of Kissam Lane, a primary school in Glen Head, New York, depicts a Circle Round focused on a blackboard and composed of curved tables meant to sit two students per desk.14 The lower right corner of the picture reveals another Circle Round configuration, this one with its back to the other. Kissam Lane's much larger classroom than Pocantico Hills facilitated two groups receiving instruction simultaneously. This school (designed by CRW), and also published in Architectural Record, sent two design messages to architects. One is the reiteration of the Circle Round practice. The second is a large classroom in which two Circle Rounds operate together.

Not all schools were as generously proportioned as the Kissam Lane School; Hilltop Elementary School (1960) in Wyoming, Ohio, just north of Cincinnati, shows options for the Circle Round arrangement when less space is available. Rather than being arrayed in a semi-circle, the children are seated in a more linear U-shape. The desks are similar to those seen in the Pocantico Hills School; each individual desk was lightweight, mobile, and easily reconfigured into a variety of seating patterns. According to the article, "all areas [of the school] are of adequate size to function efficiently."15 The image shows the students turned to face the far corner of the room, where the teacher sits at a piano. Behind the piano, on the wall toward which all of the desks are positioned, is a chalkboard. The photograph is posed (the guard over the piano's keyboard is down). It assumes that, when teaching a class, the instructor is typically at the blackboard. Circle Round's intention is to purposefully direct students' forward, so one assumes that in reality the teacher would not have configured her students into this shape, only to have them turned backwards as they are in this photograph.

The Chippewa Middle School (1962) in Saginaw Township, Michigan illustrates the "open end" classroom designed by CRS. Such a classroom was part of a movement in educational theory that called for classrooms with "large open spaces with no fixed interior elements [and] operable partitions, demountable partitions, rolling cabinet or screen units, [that] divide or shape [the] open plan to fit the [school's] program." The photograph shows a group of students seated at desks that were arranged into concentric, circular rows around the center of the classroom. At the front of the classroom, the teacher stands near her blackboard. Similar to Hilltop, the students crane their heads to see the instructor. The set up of the classroom in this instance was most likely temporary and for a specific purpose, such as a "dramatization... a wonderful learning medium as well as a splendid opportunity for self expression." Although the desks formed a nearly complete circle, it is considered a variation of Circle Round, because the desks are organized to focus on a central point in the classroom.16

The Henry M. Gunn Senior High school in Palo Alto, California utilized Marching Round in 1965 in one of its many classrooms. An image from this school features desks curved in arched rows around a corner of the room. Unlike previous examples, these desks are attached to their chairs. At the front corner of the room are two chalkboards, as well as some storage and a single desk that appears to have been used as a podium for class lectures or speeches.17

In 1972, Durham Anderson Freed designed three elementary schools, Maple, Beacon Hill and Commodore Kimball Schools, within one school district in Seattle, Washington. These open plan schools provided for each group of students a "‘learning station' with two walls (for black-and-tack board use) and a common area." One of the elementary schools photographed in Architectural Record's special issue (New Ideas in Education Ask New Planning Solutions for Schools) exemplified a new popular style of learning. Designed to "permit flexible grouping of both pupils and schedules... each group of three [teaching] stations is oriented to the resource center, facilities use." This picture is important, because it illustrates another instance of Circle Round, and also because it demonstrates the need for a very focused individual environment within an open plan. In the background of the image, a second class can be seen, also seated in Circle Round, and also grouped around its instructor.18

A photograph of a classroom in the Wilbur Cross- East Rock School (1976) in New Haven, Connecticut illustrates the furniture manufacturers' contribution to the continuation of two educational and design practices, namely, the open plan and Circle Round. The image also reveals the use of a new desk shape, the isosceles trapezoid, to facilitate Circle Round and a variety of other configurations. Trapezoidal tables were thought to be "particularly useful since [they] allow for grouping in a variety of configurations." These tables facilitated multiple configurations throughout the school, providing for a variety of environments and interactions. The manufacturer, American Seating, and the unidentified manufacturer who produced the curved desks in the Kissam Lane School (1957) enabled both teachers and students to define or redefine the shape of their classrooms. These trade sources also reinforced concepts from architects, designers and educators about what a successful classroom should be. This is fitting as this school was built to focus "not only as an academic facility but also as a community recreation and service center for the surrounding neighborhood." The photograph (Figure 3.9) is of a "conventional classroom space" with desks in curved rows face toward one of the room's tack board surfaces. According to the article, "in the interior design and space planning, flexibility for future expansion and changing classroom situations was the major objective." The library space used by the "lower grades" had no tables, just simple chairs informally grouped around a large chair for the teacher.19

By late in the decade of 1980, another Circle Round reiteration brought the archetypical practice back full circle to its amphitheater origins. Architects Earl R. Flansburgh Associates created an amphitheater space for the Arlington Elementary School in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Flansburgh's interpretation resulted in a circular configuration of tiered and carpeted fixed seats (that also served as steps) located around an open space in the school's center. This recurrence of the amphitheater concept heralded a more traditional turn in school design that replaced the "imaginative school planning" that became de rigueur in the decade of the 1960 and of 1970.20 Although the amphitheater was a group space, it was the antithesis of the flexible and movable furniture that emerged in the 1950s in response to the open plan. Nevertheless, the amphitheater, also dependent on a Circle Round concept, represents a new kind of dynamic environment, a dedicated space for teachers and students to put on presentations and plays. The size of also allowed for a variety of uses, as it can easily accommodate both larger and smaller groups.

In 1999, the Wilbert Snow Elementary School was updated to better integrate the buildings that made up the large, several-building campus. The original school "was built in 1954 [and] embodied the era's progressive thinking regarding modern architecture's role in public education."21 Like the Arlington Elementary School, Wilbert Snow also contained a more permanent variation of Circle Round. In the elementary school's library, two rows of curved step seating are nestled behind similarly curved bookshelves, creating a dedicated story-reading space. Setting this configuration apart from the rest of the library, a separate purposeful Circle Round space was created. As in the Wilbur Cross- East Rock School, this library space once again demonstrated the need for a focused environment within a larger space.

Between 1980 and 2000, Circle Round almost faded from publications, but in 2006, it was revived for the Reece School for children "with emotional disorders, learning disabilities, and speech or occupational impairments." These unique student needs called for specialized classrooms designed to accommodate "six to eight students and two teachers."22 Combining three sets of two rectangular desks, a U-shaped seating arrangement was formed, allowing students to focus on the chalkboard in front of them. Once again, Circle Round emerged as the appropriate organization for creating a supportive and distraction-free environment.

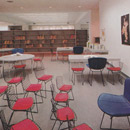

Circle Round was also found in the classrooms of the Flint Hill School in Oakton, Virginia, during a site visit in August 2012; the school itself was constructed in 2001. Both a more formal arrangement and evidence of a less formal Circle Round were found in the classrooms there. The more formal arrangement shows desks arranged in three straight rows arrayed in a U-shape and facing the center of the ninth grade English classroom. Each row is composed of approximately six or seven desks with chairs pulled up to them.23

The less formal arrangement is found in a tenth grade science classroom where seats with desks attached are circled around a lecturn at the center of the room. There appears to be an adjacent arrangement of tables in the back of the classroom as well.

Conclusion

Circle Round is a specific interior design solution that responded to educational research. Now in its sixth decade, it is used less frequently, but has not entirely faded from use. It remains an acceptable practice in both educational and architectural professions.23

end notes

- 1) Marching Order is a sequence of repeating forms organized consecutively, one after another, that establish a measured spatial order. It has been established as an archetypical practice in retail, showroom and workplace design. The Interior Archetypes Research and Teaching Project, Cornell University, http://www.intypes.cornell.edu/intypesub.cfm?inTypeID=95 (accessed May 29, 2012).

- 2) The Intype Two by Two is a furniture arrangement that pairs two people into a small working group with a two-person table or by pushing two tables side-by-side. It has been established elsewhere in this thesis as an archetypical practice in 1-12 schools.

- 3) The Intype Shuffle is an informal seating group composed of lightweight backless seat-furniture that can be rearranged easily to produce a random order. Shuffle accommodates a variety of group sizes and spatial configurations and implies mobility, flexibility and open authorship of a space for temporary seating purposes. Carla Wells, "Theory Studies: Bar and Club Design," (M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2012); Intypes Research and Teaching Project, http://www.intypes.cornell.edu/expanded.cfm?erID=214.

- 4) B.H. Stricken, "The Origin of the Greek Theatre," The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 41 (Dec. 1955): 35; Michael Forsyth, Auditoria: Designing for the Performing Arts (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1987), 12.

- 5) Stricken, The Origin of Greek Theatre, 36; Margarete Bieber, The History of the Greek and Roman Theatre, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1939), 54.

- 6) Forsyth, Auditoria, 12.

- 7) Forsyth, Auditoria, 12.

- 8) Forsyth, Auditoria, 14.

- 9) American Association of School Administration, Open Space Schools (Washington, DC: sAmerican Association of School Administrators, 1971), 33.; Francis D.K. Ching, Architecture, Form, Space & Order, Second Edition, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.,1996), 39.

- 10) Rotraut Walden, Schools for the Future: Design Proposals from Architectural Psychology (Germany: Hogrefe and Huber Publishers, 2009), 90.; American Association of School Administration, Open Space Schools, 33.

- 11) William W. Caudill, Toward Better School Design (Ann Arbor, Mich.: FW Dodge Corp, 1954), 13-14,17.

- 12) Caudill, Toward Better School Design, 28.

- 13) Pocantico Hills Central School [1956] Perkins + Will, architect; Pocantico, NY in "Schools," Architectural Record 119, no. 4 (Apr. 1956): 239-242; PhotoCrd: Hedrich-Blessing.

- 14) Kissam Lane School [1957] Caudill, Rowlett, Scott & Associates; Glen Head, NY in "Importance of Quality Design," Architectural Record 121, No. 4 (Apr. 1957) 242-243; PhotoCrd: Lawrence S. Williams.

- 15) Hilltop Elementary School [1960] Charles Burchard, A.M. Kinney Associates, architects; Wyoming, Ohio in "Campus School in Scale for Small Children," Architectural Record 127, no. 5 (May 1960): 202-205; PhotoCrd: Joseph W. Molitor.

- 16) American Association of School Administration, Open Space Schools, 33.; Chippewa Middle School [1962] Caudill, Rowlett, Scott & Associates; Saginaw Township, MI in "Caudill's Two Middle Schools are Completed," Architectural Record 131, No. 2 (Feb. 1962): 136-137; PhotoCrd: Bradford-LaRiviere, Inc.; Caudill, Toward Better School Design, 29.

- 17) Henry M. Gunn Senior High School [1965] Ernest J. Kump Associates, Inc., architects; Palo Alto, CA in "High School: Educational Reform and its Architectural Implications," Progressive Architecture 46, no. 8 (Aug. 1965): 141; PhotoCrd: William C. Eymann.

- 18) Maple, Beacon Hill, & Commodore Kimball School [1972] Durham Anderson Freed Company, P.S. Architects; Seattle, WA in "Alcoves Provide Each Learning Station with Two Walls for Teaching," Architectural Record 152, no. 2 (Aug. 1972): 107-109; PhotoCrd: Hugh Stratford Photos.

- 19) Wilbur Cross- East Rock School [1976] Edward Larabee Barnes, architect, ISD Incorporated with Mary Barnes, interiors: "Wilbur Cross- East Rock School," Interior Design 47, no. 8 (Aug. 1976): 106-111; PhotoCrd: Jaime Ardiles-Acre.

- 20) Arlington Elementary School [1988] Earl R. Flansburgh Associates, Inc., architects; Lawrence, MA in "Varied Textures and Subtle Color Enrich a Conservative Pattern," Architectural Record 176, no. 10 (Sep. 1988): 112-13; PhotoCrd.: Sam Sweezy Photos.

- 21) Wilbert Snow Elementary School [1999] Jeter, Cook & Jepson, Architect; Middletown, CT; "Open Door Policies: Wilbert Snow School, Middletown, Connecticut," Architectural Record 187, no. 9 (Sep. 1999): 118- 121; PhotoCrd: Woodruff/Brown Photography.

- 22) The Reece School [2007] Platt Byard Dovell White Architects; New York City, NY in "Making the Grade: The Reece School, New York City," Architectural Record 195, no. 7 (Jul. 2007): 140-144; PhotoCrd: Jonathan Wallen.

- 23) SIte Visit, Katherine Mooney, 13 August, 2012; PhotoCrd: Katherine Mooney, Intypes Project, 13 August, 2012.

- 24) Evidence for the archetypical use and the chronological sequence of Circle Round in school design was developed from the following primary sources: 1950 Pocantico Hills Central School [1956] Perkins + Will, architect; Pocantico, NY in "Schools," Architectural Record 119, no. 4 (Apr. 1956): 242; PhotoCrd: Hedrich-Blessing.; Kissam Lane School [1957] Caudill, Rowlett, Scott & Associates; Glen Head, NY in "Importance of Quality Design," Architectural Record 121, No. 4 (Apr. 1957) 243; PhotoCrd: Lawrence S. Williams.; 1960 Hilltop Elementary School [1960] Charles Burchard, A.M. Kinney Associates, architects; Wyoming, Ohio in "Campus School in Scale for Small Children," Architectural Record 127, no. 5 (May 1960): 205; PhotoCrd: Joseph W. Molitor.; Chippewa Middle School [1962] Caudill, Rowlett, Scott & Associates; Saginaw Township, MI in "Caudill's Two Middle Schools Are Completed," Architectural Record 131, No. 2 (Feb. 1962): 137; PhotoCrd: Bradford-LaRiviere, Inc.; Henry M. Gunn Senior High School [1965] Ernest J. Kump Associates, Inc., architects; Palo Alto, CA in "High School: Educational Reform and its Architectural Implications," Progressive Architecture 46, no. 8 (Aug. 1965): 141; PhotoCrd: William C. Eymann.; 1970 Maple, Beacon Hill, & Commodore Kimball School [1972] Durham Anderson Freed Company, P.S., architects; Seattle, WA in "Alcoves Provide Each Learning Station with Two Walls for Teaching," Architectural Record 152, no. 2 (Aug. 1972): 109; PhotoCrd: Hugh Stratford Photos.; Wilbur Cross- East Rock School [1976] Edward Larabee Barnes, architect, ISD Incorporated with Mary Barnes, interior design; New Haven, CT in "WilburCross- East Rock School," Interior Design 47, no. 8 (Aug. 1976): 109; PhotoCrd: Jaime Ardiles-Acre.; Wilbur Cross- East Rock School [1976] Edward Larabee Barnes, architect, ISD Incorporated with Mary Barnes, interior design; New Haven, CT in "WilburCross- East Rock School," Interior Design 47, no. 8 (Aug. 1976): 110; PhotoCrd: Jaime Ardiles-Acre.; 1980 Arlington Elementary School [1988] Earl R. Flansburgh Associates, Inc., architects; Lawrence, MA in "Varied Textures and Subtle Color Enrich a Conservative Pattern," Architectural Record 176, no. 10 (Sep. 1988): 112; PhotoCrd.: Sam Sweezy Photos.; 1990 Wilbert Snow Elementary School [1999] Jeter, Cook & Jepson, Architect; Middletown, CT; "Open Door Policies: Wilbert Snow School, Middletown, Connecticut," Architectural Record 187, no. 11 (Nov. 1999): 121; PhotoCrd: Woodruff/Brown Photography.; 2000 The Reece School [2007] Platt Byard Dovell White Architects; New York City, NY in "Making the Grade: The Reece School, New York City," Architectural Record 195, no. 7 (Jul. 2007): 143; PhotoCrd: Jonathan Wallen.; The Flint Hill School [2001] Chatelain Architects; Oakton, VA; SIte Visit, Katherine Mooney, 13 August, 2012; PhotoCrd: Katherine Mooney, Intypes Project, 13 August, 2012; The Flint Hill School [2001] Chatelain Architects; Oakton, VA; SIte Visit, Katherine Mooney, 13 August, 2012; PhotoCrd: Katherine Mooney, Intypes Project, 13 August, 2012.

bibliographic citations

1) The Interior Archetypes Research and Teaching Project, Cornell University, www.intypes.cornell.edu (accessed month & date, year).

2) Mooney, Katherine Elizabeth. "Theory Studies: Archetypical Practices in American K-12 Schools." M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2012, 60-83.