Notch

Notch is a circulation strategy in which a long corridor wall is broken by a line of shallow recesses that indicate a door opening. Notch includes single or double entries and aligned or staggered placements. more

Notch | Hotel

application

In a hotel, guest room doors are recessed from the corridor's wall plane with an alcove that reduces the visual length of a hall and gives each guest room a sense of entry.

research

Hotel halls can be quite long and feel institutional, but by interrupting the wall from one expansive plane into one with indentations, the hall appears to be divided into sections. Notches vary in size, shape, and depth, but each alcove is formed in a subtractive manner: square footage that is lost from the suite is gained by the corridor.

Notches not only break up the monotony of the corridor, but they also serve another strategic purpose: to provide a transition space in connection with the guestrooms. The additional step in the sequence of entering and exiting the room gives each room greater perceived privacy and individuality.1 The Notch serves as a shallow vestibule.

Depending on the configuration and orientation of the guestrooms, a single Notch can serve either one room or two rooms. When the corridor is double-loaded, two Notches may be situated directly across from one another in order to produce a greater-articulated break in the hall, creating an implied room within the circulation space. These Notches, however, provide a lesser impression of privacy and individuality than another strategy: staggering the Notches on opposing walls.2

Additional strategies also further modulate halls. The basic corridor alcove that creates a Notch is often coupled with ceiling heights, lighting plans, flooring, and treatments that differ from those in the adjacent corridor.3

Chronological Sequence

When air travel became the preferred mode of long-distance travel after World War II, hotel chains expanded nationally and internationally with great success. Chains promoted a desired constant in quality, service, and décor regardless of their location. Hilton, one of the era's most successful chains, incorporated this expected familiarity into their International Style hotel architecture. For example, the Istanbul Hilton (1955) incorporated "modern materials, boxy forms, bright lighting, and interior shopping arcades" that "identified the Hilton as a contemporary expression of American-led global culture."4

Following Hilton's lead, the world's new commercial hotels shed regionalist aesthetics in order to attract a more international clientele. For the first time, hotels around the world began to assimilate to a universal, research-influenced hotel typology. It was during this era continuing through the 1960 decade that the archetypical practice for modulating corridors with Notches became prevalent.

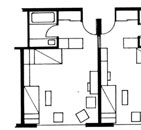

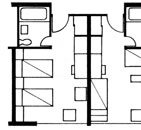

Notch became so common, in fact, that books such as Principles of Hotel Design (1970, Architects' Journal) featured the strategy in more than three-quarters of their proposed room layouts. The authors advised: "To avoid an institutional appearance corridors should be modulated or not be too long. Modulation can be achieved by recessing certain elements of the bedroom (generally the lobby) and using different heights of false ceilings with variation of the light intensity in the corridor."5 The book featured two variations of the dual-entry Notch.6

A Notch layout similar to those of Principles of Hotel Design appeared in the 1974 redesign of the Caribe Hilton Hotel Tower in San Juan, Puerto Rico. The interior designer, Bill Boydston, strove to make the hotel's 221 regular guest rooms and circulation spaces less commercial. Specifically, he decreased the perceived length of the corridors to a more residential proportion. By creating aligned Notched guestroom entries in the double-loaded corridors, he segmented the corridor alternating between Notch vestibules and the hall that connected them.7 Custom carpeting was employed to visually differentiate sections of the hallway. In-between the aligned Notches was a wider, less dense carpet pattern than in the adjacent sections of the hall. The change in pattern further enabled space between the two aligned notches to be identified as one zone rather than two separate alcoves.8

In the chronological sequence of the Intype's development, Notches took various forms. In the Marquette Inn IDS Center (1978) in Minneapolis, setbacks on the building's exterior were reflected in its interior corridor.9 This gave most rooms a corner view and the zig-zag pattern in the corridor created an sculptural throughway.10

It was not uncommon for a hotel to use different versions of Notch simultaneously in one corridor. Campton Place hotel in San Francisco was one that employed both single-entry Notches and dual-entry Notches. Redesigned by Hirsch/Bender in 1985, double rooms adjacent to single rooms (that could be internally connected to create a suite) shared dual-entry Notches. Single rooms that could not be connected to other rooms featured their own single-entry Notch, and the majority of the notches were staggered.11

In 1988 the Grand Hotel Esplande opened in Berlin after two years of construction. Featuring 402 guestrooms, the triangle-shaped structure featured two perpendicular wings that housed the guestrooms while its public spaces occupied the space between them. The wings were common double-loaded corridors featuring aligned dual-entry Notches. The interior design firm Gernot et Johanne Nalbach further enhanced the Notched corridors by incorporating a dramatic lighting scheme with Hotspots (Intype),12 lowering the ceiling height in the throughways between Notches, and by changing the carpeting hue between the Notches.13 These dramatic elements introduced to an otherwise generic hall identified each space between the aligned Notches as a chamber of its own.

Curving the corridors on guest room floors was another strategy to visually eliminate the oppressive length associated with straight hallways;14 the curvature prevents one from being able to view the corridor in its entirety. One of the earliest and most famous hotels to do so was Miami's Fontainebleau (1953). Almost fifty years later and across the globe, the Fit Resort Club in Kawaguchiko-cho, Japan coupled a similar curved corridor with single-entry Notches to engender a significant sense of privacy for each guestroom entrance.15 Located at the base of Mount Fuji, and integrated with its natural surroundings, the design of the hotel sought privacy and serenity.

The Clarion Hotel, a small urban resort hotel, opened in Kurashiki, Japan during the same year. The establishment had a single-loaded corridor of guestrooms on each floor; the other side of the hall was open to the hotel's full-height atrium. Individual Notches for the standard rooms were situated around squared structural columns and were deeper than they were wide.16 These alcoves created true vestibules for each suite and provided a significant level of graduated privacy.

In 2008 the Emperor Hotel, a sixty-room boutique hotel, opened in the heart of Beijing. Designed by Graft (known for Hotel Q! in Berlin [2004]), the Emperor was defined by bright, animated interiors. Rather than minimizing the length of its corridor, the designers emphasized that which so many other hotels sought to diminish. The corridor was comprised of one uninterrupted run of carpet stretching the length of the hall, generous-sized Notches with wood floors on either side of the carpet, various lighting schemes, and contrasting wall treatments that made the hallway a significant architectural space.17 The main pathway was so well articulated with its flooring and Follow Me (Intype)18 lighting scheme, that stepping from it into a Notch - with its wooden floor, colorful soffit, and soft downlighting - created the perception of leaving an expansive space (the corridor) and entering into a small space (a vestibule).

Another high-design hotel completed in 2008 was the Urbn hotel in Shanghai. The four-story structure was a former factory and office before becoming its newest iteration at the hands of A00 architects. The hotel's guestroom corridors featured some Notches and were finished in rich materials: repurposed mohagany and brick from demolished local buildings.19 Regardless of if they are in a Notch, the doorways to the rooms are unique to the hotel because one must step over a raised threshold to enter a room. The use of the step is common in Chinese residential vernacular; it emphasises the transition of leaving one space and entering another.

Conclusion

Historically, Notch, as a circulation strategy, was employed to solve two problems-mitigating the visual length of a long corridor, and providing a sense of individuality and privacy for each person's guestroom door. In the 2000 decade, however, Notch became one of many tactics used to transform an ordinary corridor from a dead space, visually and physically, into a dynamic architectural space, exemplified by two 2008 hotels in China-the Emperor in Beijing and the Urbn in Shanghai.20

end notes

- 1) Fred Lawson, Hotels, Motels and Condominiums; Design, Planning and Maintenance (London, England: The Architectural Press, Ltd., 1976), 156.

- 2) Lawson, Hotels, Motels and Condominiums, 156.

- 3) The Architects' Journal, ed., Principles of Hotel Design (London, England: The Architectural Press, 1974), 68.

- 4) Donald Albrecht, New Hotels for Global Nomads (London, England: Merrell Publishers Limited, 2002), 22.

- 5) The Architects' Journal, Principles of Hotel Design, 68.

- 6) Typical Hotel Room Plans, in The Architects' Journal, ed., Principles of Hotel Design (London, England: Architectural Press, 1970), 66.

- 7) Corridor, Caribe Hilton Tower [1974] Bill Boydston, Interior Design; Toro & Ferrer, Architecture; San Juan, Puerto Rico in Anonymous, "Caribe Hilton Tower," Interior Design 45, no.4 (Apr. 1974): 151.

- 8) "Caribe Hilton Tower," 150-51.

- 9) Corridor, Marquette Inn [1978] Anonymous, Interior Design; Johnson/Burgee, Architects; Minneapolis, MN in Henry End, Interiors 2nd Book of Hotels (New York City: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1978), 99.

- 10) End, Interiors 2nd Book of Hotels, 99.

- 11) Floor plan, Compton Place [1985] Hirsch/Bender, Interior Design; Anonymous, Architecture; San Francisco, CA in Anonymous, "Improved with Age," Interior Design 56, no.1A (Jan. 1985): 224.

- 12) Intypes researcher Joanne Kwan identified Hotspot in her 2010 lighting design study. Hotspot is an isolated pool of bright downlight that operates in contrast to its surroundings. Hotspot encourages a pause in movement and collection around or within it. It is achieved with a single spot light or a single fixture on a light track. See Joanne Kwan, "Theory Studies: Archetypical Artificial Lighting Practices in Contemporary Interior Design," (M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2010), 41-51.

- 13) Corridor, Grand Hotel Esplanade [1988] Gernot et Johanne Nalbach, Interior Design; Jürgen J. Sawade, Axel Shultz, Architecture; Berlin, Germany in Brigitte Fitoussi, Hôtels (Paris, France: Editions du Moniteur, 1992), 70.

- 14) Jeffrey Limerick, Nancy Ferguson, and Richard Oliver, America’s Grand Resort Hotels (New York City: Pantheon Books, 1979), 245.

- 15) Floor Plan, Fit Resort Club [1992] Media Five, John Chan Design, Ltd., Interior Design; Kume Sekkei Co., Ltd., Architecture; Kawaguchiko-cho, Japan in Meisei Shuppan, New Hotel Architecture: Modern Hotel Design: A Pictorial Survey (Tokyo, Japan: Meisei Publications, 1993) 134.

- 16) Floor Plan, Clarion Hotel [1992] F&N Architect Associates, Mitsukoshi, Ltd., Interior Design; F&N Architect Associates, Architecture; Kuraskiki, Japan in Meisei Shuppan, New Hotel Architecture: Modern Hotel Design: a Pictorial Survey (Tokyo, Japan: Meisei Publications, 1993), 75.

- 17) Corridor, Emperor Hotel [2008] Graft, Interior Design; Graft, Architecture; Beijing, China in Fred A. Bernstein "Dynastic Ambitions," Interior Design 79, no. 8 (Jun. 2008): 281.

- 18) Intypes researcher Joanne Kwan identified Follow Me in her 2010 lighting design study. Follow Me describes sequenced pools of light on the floor that are in contrast with the surrounding space, defining a circulation path. See Joanne Kwan, "Theory Studies: Archetypical Artificial Lighting Practices in Contemporary Interior Design," (M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2010), 52-66.

- 19) Corridor, Urbn Hotel [2008] A00, Interior Design; Anonymous, Architecture; Shanghai, China in Catherine Sole, "Letter from Shanghai: A00 Architecture and Studio 1:1 Have Transformed a Post Office into the Premier Property of Urbn Hotels & Resorts," Interior Design 79, no.9 (Jul. 2008): 274.

- 20) Evidence for the archetypical use and the chronological sequence of Harlequin in hotels was developed from the following sources: 1970 Typical Hotel Room Plans, in The Architects' Journal, ed., Principles of Hotel Design (London, England: Architectural Press, 1970), 66; ImageCrd: Anonymous; Corridor, Caribe Hilton Tower [1974] Bill Boydston, Interior Design; Toro & Ferrer, Architecture; San Juan, Puerto Rico in Anonymous, "Caribe Hilton Tower," Interior Design 45, no.4 (Apr. 1974): 151; PhotoCrd: Anonymous; Corridor, Marquette Inn [1978] Anonymous, Interior Design; Johnson/Burgee, Architects; Minneapolis, MN in Henry End, Interiors 2nd Book of Hotels (New York City: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1978), 99; PhotoCrd: Philip MacMillan James & Associates / 1980 Floor plan, Compton Place [1985] Hirsch/Bender, Interior Design; Anonymous, Architecture; San Francisco, CA in Anonymous, "Improved with Age," Interior Design 56, no.1A (Jan. 1985): 224; ImageCrd: Hirsch/Bender; Corridor, Grand Hotel Esplanade [1988] Gernot et Johanne Nalbach, Interior Design; Jürgen J. Sawade, Axel Shultz, Architecture; Berlin, Germany in Brigitte Fitoussi, Hôtels (Paris, France: Editions du Moniteur, 1992), 74; PhotoCrd: P. Bartenbach, R. Görner / 1990 Floor Plan, Fit Resort Club [1992] Media Five, John Chan Design, Ltd., Interior Design; Kume Sekkei Co., Ltd., Architecture; Kawaguchiko-cho, Japan in Meisei Shuppan, New Hotel Architecture: Modern Hotel Design: A Pictorial Survey (Tokyo, Japan: Meisei Publications, 1993) 134; ImageCrd: Kume Sekkei Co., Ltd.; Floor Plan, Clarion Hotel [1992] F&N Architect Associates, Mitsukoshi, Ltd., Interior Design; F&N Architect Associates, Architecture; Kuraskiki, Japan in Meisei Shuppan, New Hotel Architecture: Modern Hotel Design: a Pictorial Survey (Tokyo, Japan: Meisei Publications, 1993) 75; ImageCrd: F&N Architect Associates / 2000 Corridor, Emperor Hotel [2008] Graft, Interior Design; Graft, Architecture; Beijing, China in Fred A. Bernstein "Dynastic Ambitions," Interior Design 79, no. 8 (Jun. 2008): 281; PhotoCrd: Hong Chao Wai; Corridor, Urbn Hotel [2008] A00, Interior Design; Anonymous, Architecture; Shanghai, China in Catherine Sole, "Letter from Shanghai: A00 Architecture and Studio 1:1 Have Transformed a Post Office into the Premier Property of Urbn Hotels & Resorts," Interior Design 79, no.9 (Jul. 2008): 274; PhotoCrd: Nobuko Ohara/ Nacása & Partners.