halo

Halo exists when an object is visually separated from a background plane through a concealed light. Illumination occurs on the background plane behind the majority of the perimeter of the object, thus throwing the object into relief. more

halo | Light

research

Halo is the effect created by backlighting at least half the perimeter of an object, visually lifting it from its surroundings.

In the 2004 retail study, the Intypes researcher Leah Scolere identified a lighting type that she named Light Contour. She defined Light Contour as "a cove detail that illuminated a form on the ceiling plane. By creating a highly illuminated area on the ceiling plane, Light Contour organizes and draws attention to the space beneath it."1 In this study I argue that while Light Contour defines a line that produces an identifiable light gradient to one side, it does not necessarily suggest shape and form, including both positive forms (mass) and negative shapes (void). Both Halo and Light Contour are concealed lighting and use some kind of cove detail, but Halo highlights an advancing form by creating an outer glow around it, while Scolere's examples of Light Contour primarily accentuate the shape of a recessed ceiling plane, creating an inner glow to the overall ceiling. The practices provide different indications of motion.

Effects

Halo highlights the shape of an object and visually pushes it forward from the background, giving the forward plane hierarchical priority.

Halo is created by placing lights at the back of the object close to the perimeter. This involves leaving a gap between the edges of the top plane and supporting structure. Light installed at the gap emanates a glow that obscures the supporting structure and emphasizes the separation between the planes. In Light Revealing Architecture author Marietta Millet describes this phenomenon as light concealing structure, because the plane appears to contradict the rules of structural support and float over the light.2 White or warm-colored lights appear to expand and strengthen a floating effect.3

Halo accentuates the movement introduced by the forward object, adding to the dynamic quality of the space. Halo has been employed on both horizontal and vertical surfaces, but appears the most dramatic when positioned at the floor plane where gravity has a dominating presence. Materials and dimensions of objects affect the perceived weight of the mass and influence the level of drama. Halo is most often used to accent the form of raised platforms or lowered ceilings, enhancing their space-defining qualities. The light draws attention to the area enclosed by the shape, transforming actions within into a staged scene.

Chronological Sequence

In the 1930s, the concept of indirect lighting was widely embraced for its "sight-saving" qualities.4 Concealed lighting practices expanded further with the commercialization of tubular lights, especially the more economical fluorescent lamps that soon became standard for commercial and institutional interiors. While the architecture was designed to hide the tube lights, light in turn directly impacted its representation through contours of light that reveal the shape of architectural forms. By highlighting their shape, concealed lighting also drew attention to the relationship between the forms and their surroundings. The comparatively low-cost of concealed lighting employing fluorescent lamps first attracted use in large spaces, where an unobtrusive glow highlighted architectural forms and brought additional interest to the interior.

It was in the retail interior where designers began experimenting with light quality (as long as it maximized spatial areas and did not distract from the merchandise). In the Ansonia Shoe Store in New York City (1945), designer Morris Lapidus projected backlit displays with frames from the surface of the wall to display merchandise and to keep consistent light gradients throughout the space.5 Compared with a traditional niche that recessed the merchandise from the customers, Lapidus' Halo effect for frames pushed merchandise toward customers, creating a museum-like vitrine. Goods framed by a Halo captured and held people's attention momentarily, before they moved on to the next successive frame. Many shops at the time used backlighting on the top edges of display cabinets along the walls to draw customers towards the displays at the periphery. In the Mangel store (1946) in Birmingham, Alabama, Lapidus used a Halo to highlight a curved ceiling. This feature defined a spatial area towards the back of the store, conveying the store organization, and breaking up a large space.6

From the 1940s to late 1950s, artificial lighting design, especially indirect lighting design, was still in its infancy. The quantity of light sources, rather than the quality of light, remained the primary concern of designers. The concept of qualitative lighting design barely existed, and both socially and functionally, more non-distracting, uniform illumination was considered to be the best lighting. For commercial interiors, this meant lighting from the ceiling plane. Therefore, most of the early examples of concealed lighting were found at the ceiling plane, equally distributed around the perimeter walls where soffits for up-lighting could be easily built. They otherwise appeared as suspended grid structures for up-lights, spanning across a gridded ceiling that corresponded to column locations. Using fluorescent tubes, these structures provided general illumination at an economical cost for an entire space.

Lighting designer and consultant Richard Kelly dedicated his professional life to the advancement of lighting design, championing an integral relationship between lighting and architecture. Kelly opened one of the first lighting consultancies in 1935 in New York City. By the early 1950s, Kelly introduced the idea of different purposes of light, encouraging designers to break away from uniform luminance as the paramount criterion of lighting interiors. His vocabulary for modern architectural lighting design included three light energy impacts: focal glow (highlight), ambient luminescence (graded washes), and play of brilliants (sharp detail).7

By the late 1950s, designers realized the expressive potential of an up-lit ceiling, and by the 1960s, they began to suspend ceiling forms in large spaces to differentiate spatial areas (as Lapidus had done in the 1940s). A good example of this thinking occurred In the First Methodist Church of Wichita. A halo of light provided a delicate floating quality to the fish-shaped ceiling slab.8

From the 1960s to 1970s, several developments in lighting gradually changed the quantitative mindset that designers held towards lighting. Building on Richard Kelly's legacy, by the early 1960s the work of theatre lighting designers who ventured into the architecture industry gave rise to the new profession of architectural lighting designers, and in turn, this group created a general awareness towards the expressive potentials of lighting. In 1966 the first comprehensive exhibition of light art, KunstLichtKunst, introduced the new field in which artists experimented with the quality of light. The exhibition validated and encouraged expressive potentials of light.9 Outside the museum walls, the expanding nightclub culture used light as one of its main devices. With the abrupt end of the disco culture in late 1979, however, practices of placing lighting on the floor were suspended. Concealed lighting in the 1980s appeared primarily as Light Seams, or series of parallel light contours that divided up the plane and also served as part of the general illumination.

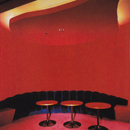

In the 1990s and 2000s, the minimalism aesthetic increased opportunities for the use of Halo as designers experimented with using different light sources in the same space. Two excellent examples illustrate the application of Halo at the ceiling plane; one with a warm light, the other with cool light. Totah Design, an architectural and interior design firm in Tokyo, relied on Halo for the lighting and architectural effects in the Odeum Karaoke Club. The firm utilized an amber Halo for an organically shaped ceiling form projecting from the ceiling of a Red Room.10 For an office interior, Vienna based architects Baumschlager, Eberle, Grassman "suspended an elliptical cloud, backlit it in white cold cathode and dotted it with cone-shaped down light" in the Dornbirn office of the lighting firm, Zumtobel.11

With the introduction of LEDs, designers from all fields leaped at the new possibilities the technology offered. Halo exploited the compactness of the newer light sources and emerged as a new way of emphasizing the smaller architectural forms introduced in the mid-1990s to break up minimalist spaces.

In the Costume National in Los Angeles (2001), garments along the wall were framed by backlit white rectangular panels in a White Box interior. The Halo of white light accented the whiteness of the interior, while floating display panels enhanced the airy quality of the space.12

The small size of LEDs ushered in renewed interest in the Halo effect near the floor level. In the Australian Center for the Moving Image at Melbourne's Federation Square, a round conversational area seems to hover above the floor plane. The Halo effect was heightened by the low general illumination in the gallery.13

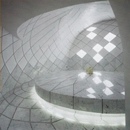

The Halo practice was used frequently in the 2000s as a means to give form and movement to a ceiling. At the lobby atrium at Top of the Rock, Halo brings an air of restraint around the oval ceiling that builds up inwards and upwards to provide a shower of brilliant crystals raining down from the center of the atrium.14

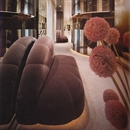

Halo produces dramatic spaces when heavy objects are lit to levitate them from the floor plan. Two examples demonstrate this juxtaposition between visual weight and floatation. In the first example, Halo added a whimsical touch to the "hot tub" seating area of a lunchroom in the Toronto office of Grip Limited Creatives. The large mass appeared to be suspended above floor level, making it the center of attention, a stage for socializing with colleagues.15

Recently designers have begun to fine-tune the degree of movement introduced by Halo through experiments with material, edge detail, choice of light source and its placement relative to the planes. Color coordination also became a point of interest as a variety of colors introduced different kinds of energy to the space.

The development of Halo shows an example where new lighting use is encouraged by the coming of new technology, inviting new ideas for use, but also reinterpreting previous or exiting uses. It demonstrates that the development of more recent lighting design practices may be as much about finding a use rather than purely driven by need. In this sense, if Halo continues to find use, it might in time present itself as a basis for new practice types.16

end notes

- 1) Leah Scolere, "Theory Studies: Contemporary Retail Design" (MA Thesis, Cornell University, 2004), 133.

- 2) Marietta Millet, Light Revealing Architecture (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1996), 65-66.

- 3) Thomas Thiis-Evensen, Archetypes in Architecture (Oslo: Norwegian University Press, 1987), 249.

- 4) John Pile, A History of Interior Design, 3rd ed. (London: Laurence King Publishing: 2009), 368.

- 5) Anonymous, "Shop for Popular Shoes," Interiors 105, no. 3 (Oct. 1945): 60.

- 6) Ansonia Shoe Store [1945] Morris Lapidus; New York City in Anonymous, "Shop for Popular Shoes," Interiors 105, no. 3 (Oct. 1945): 60; PhotoCrd: Gottscho-Schleisner; Mangel Store [1946] Ross Frankel Inc.; Birmingham, AL in Anonymous, "Ross Frankel Designs; Ross Frankel Builds," Interiors 106, no. 5 (Dec. 1946): 93; PhotoCrd: Ben Schnall.

- 7) Rudiger Ganslandt and Harald Hofmann, Handbook of Lighting Design (Ludenscheid: ERCO Leuchten GmbH, 1992), 24.

- 8) Sanctuary, First Methodist Church of Wichita [1960] Glenn E. Benedick; Wichita, KS in Advertisement, "How G-E Remote Control Wiring Can Help You Do Dramatic Things with Mood Lighting," Architectural Record 134, no. 6 (Dec. 1963): 156; PhotoCrd: Anonymous.

- 9) Peter Weibel and Gregor Jansen, eds., Light Art from Artificial Light: Light as a Medium in 20th and 21st Century Art (Ostfildern, Deutschland: Hatje Cantz., 2006), 27.

- 10) Odeum Karaoke Club [1992] Totah Design; Tokyo, Japan in Mayer Rus, "Totah Design," Interior Design 63, no. 16 (Dec. 1992): 105; PhotoCrd: Nacasa and Partners.

- 11) Foyer, Zumtobel Offices [1994] Baumschlager, Eberle, Grassman; Lighting Consultants: Zumtobel Licht; Dornbirn, Austria in Charles D. Linn, "No Glass Ceilings," Architectural Record 182, no. 8 (Aug. 1994): 31.

- 12) Costume National [2001] Marmol Radziner + Associates, Architect; John Brubaker, Architectural Lighting Consultants; Los Angeles, CA in David Hay, "Costume National," Architectural Record 189, no. 1 (Jan. 2001): 114; PhotoCrd: Benny Chan/ Fotoworks.

- 13) Australian Center for Moving the Image, Federation Square [2003] Lab Archtiecture Studio; Melbourne, Australia in Charles Jencks, "The Undulating Federation Square," Architectural Record 191, no. 6 (Jun. 2003): 199; PhotoCrd: Gollins Photography.

- 14) Atrium, Top of the Rock [2005] Gabellini Sheppard Associates; New York City in Lily Kalmar, "Rock On," Interior Design 79, no. 12 (Jan. 2006): 212; PhotoCrd: Paul Warchol.

- 15) Hot Tub, Lunchroom, Grip Limited Creatives [2006] Johnson Chou; Toronto, Canada in "Inspiration on Tap," Interior Design 77, no.12 (Oct. 2006): 258; PhotoCrd: Tom Arban.

- 16) Evidence for the use and the chronological sequence of Halo as an artificial lighting archetype was developed from the following published trade sources: 1940 Anonymous, "Shop for Popular Shoes," Interiors 105, no. 3 (Oct. 1945): 60; Ansonia Shoe Store [1945] Morris Lapidus; New York City in Anonymous, "Shop for Popular Shoes," Interiors 105, no. 3 (Oct. 1945): 60; PhotoCrd: Gottscho-Schleisner; Mangel Store [1946] Ross Frankel Inc.; Birmingham, AL in Anonymous, "Ross Frankel Designs; Ross Frankel Builds," Interiors 106, no. 5 (Dec. 1946): 93; PhotoCrd: Ben Schnall / 1960 Sanctuary, First Methodist Church of Wichita [1960] Glenn E. Benedick; Wichita, KS in Advertisement, "How G-E Remote Control Wiring Can Help You Do Dramatic Things with Mood Lighting, " Architectural Record 134, no. 6 (Dec. 1963): 156; PhotoCrd: Anonymous / 1990 Odeum Karaoke Club [1992] Totah Design; Tokyo, Japan in Mayer Rus, "Totah Design," Interior Design 63, no. 16 (Dec. 1992): 105; PhotoCrd: Nacasa and Partners; Foyer, Zumtobel Offices [1994] Baumschlager, Eberle, Grassman; Lighting Consultants: Zumtobel Licht; Dornbirn, Austria in Charles D. Linn, "No Glass Ceilings," Architectural Record 182, no. 8 (Aug. 1994): 31 / 2000 Costume National [2001] Marmol Radziner + Associates, Architect; John Brubaker, Architectural Lighting Consultants; Los Angeles, CA in David Hay, "Costume National," Architectural Record 189, no. 1 (Jan. 2001): 114; PhotoCrd: Benny Chan/ Fotoworks; Australian Center for Moving the Image, Federation Square [2003] Lab Archtiecture Studio; Melbourne, Australia in Charles Jencks, "The Undulating Federation Square," Architectural Record 191, no. 6 (Jun. 2003): 199; PhotoCrd: Gollins Photography; Atrium, Top of the Rock [2005] Gabellini Sheppard Associates; New York City in Lily Kalmar, "Rock On," Interior Design 79, no. 12 (Jan. 2006): 212; PhotoCrd: Paul Warchol; Hot Tub, Lunchroom, Grip Limited Creatives [2006] Johnson Chou; Toronto, Canada in "Inspiration on Tap," Interior Design 77, no.12 (Oct. 2006): 258; PhotoCrd: Tom Arban.

bibliographic citations

1) The Interior Archetypes Research and Teaching Project, Cornell University, www.intypes.cornell.edu (accessed month & date, year).

2) Kwan, Joanne. "Theory Studies: Archetypical Artificial Lighting Practices in Contemporary Interior Design." M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2009, 167-82.