float

Float is a weight-bearing floor plane comprised of a translucent material that is lit from below, giving an unnatural effect. more

float | Light

research

Float was first identified as an archetypical practice in boutique hotels.1

Float may be a result of a floor slab inset with structural glass which becomes a lit floor through illumination of the level below. In recent examples, Float is constructed of translucent platforms that are deliberately built for this purpose with lamps hidden underneath the translucent planes. A few early examples of Float using constructed platforms employed incandescent light bulbs as its light source. Fluorescent tubes are used in the majority of more recent installations, because of the lower cost, non-directional light and long shape that facilitates a more even light distribution. From 2000 to 2010, LEDs were been used in a few installations. Their small size and flexible arrangement facilitated uniform light distribution even in less regular shaped platforms. More importantly, LED installations offered color-changing effects. In all types of construction, tiles of translucent glass are held in place by a structural frame. The size of the tiles, the detailing of the edge of the tiles and the way they are framed will determine how much of the frame is revealed. This affects the continuity of the appearance of the lit floor.

Effect

Most Float installations impart a diffused, even illumination from below. Large areas of up-light evoke a sense of floating. Float often becomes the center of attention. As with most lighting effects, large contrasts with general light levels create more dramatic effects, although issues of glare limit their brightness. Therefore, Float is often complemented by other sources of ambient illumination.

Part of the dramatic effect of a lit floor arises from light coming from below. This departs from our everyday experiences of the directionality of light and how shadow defines form. In the natural environment, sunlight comes from above, and it is the strongest light we encounter every day. Lighting from the moon acts similarly. The most common value pattern in nature goes from dark to light as one move from the ground below to the sky above.2 In this context, soil and stone belonging to the earth are associated with darker colors. These darker values communicate weight and stability, while lighter values communicate lightness in weight.

In this archetypical practice, these properties are reversed. Light comes from below and creates a value gradient in opposition to the norm. A brightly lit floor casts unfamiliar shadow patterns on those standing on it. Large smooth blocks of light deny substance. Standing on a lit floor is like standing on nothing; this experience evokes a sense of floating. The effect is enhanced by minimal appearance of structural frame. Architectural theorist Thomas Thiis-Evensen describes glass floors as imparting a sense of insecurity.3 Altogether, these qualities of the Float archetype create highly dramatic spaces, although numerous sources suggest that up-lights create unflattering shadows on people.4

Chronological Sequence

From the middle of the 19th century forward, developments in cast iron and glass construction introduced glass ceilings that brought natural light deep into the interior. Among the earliest of these developments were Jean-Pierre Cluysennar's arcade, the Galleries Royal Saint Hubert (1847) in Brussels and Joseph Paxton's Crystal Palace (1851) in London.

Although these examples are well known, there has been little historical research about cast iron and glass flooring, but sometime in the late 19th or early 20th centuries, cast iron grids with glass inserts were widely used for the sidewalks of New York City's SoHo area in order to bring daylight into the basement vaults. At night, light from the basements created a lit pavement on the ground level. Some of these early installations can still be seen as retailers, such as Prada (2001), bring new uses to basements.

In 1904, Otto Wagner used large amounts of glass to create a light-filled interior for the Austrian Postal Savings Bank in Vienna. Moreover, he used structural glass for the floor of the main room in order to bring natural light into the basement.5 (Fig. 1) Compared to the earlier steel grids with glass inserts, structural glass made larger expanses of a continuous glass floor possible and greatly improved the illumination in floors below. In the evening the glass floors became a lighted surface, creating a connection between the floors and expanding the perception of vertical space.

By the late 1920s, glass blocks were becoming increasingly popular materials for ceilings, walls and floors. When the luxurious Baker Hotel in St. Charles, Illinois, opened in 1928, it boasted that its ballroom floor was one of only three lighted glass floors in the world. The Rainbow Room's floor incorporated 2,620 red, green, yellow and blue lights beneath its floor of 300 glass blocks.6

In the 1930s the commercialization of tubular lighting sources, such as fluorescents, resulted in the design community shifting its attention away from color artificial lighting practices. The practice of Float almost disappeared and was not revived until the 1960 decade.7

Inspired by the first human space flight, Evelyn Jablow, a noted decorator and furniture designer, fabricated a futuristic Astrotel trade-booth for the Upholstery Leather Group in the annual Design and Decoration trade show in 1962.8 (Fig. 2) The booth was an imagined room in a space port; it was constructed entirely of glass and featured a lit translucent floor. Compared to the Austrian Post Savings Bank, the less prominent structural support created a continuous lighted plane rather than individual grids of light. Light coming from below the frosted glass suggested a sense of weightlessness in space, an illusion enhanced by furniture that was suspended from thin wire.

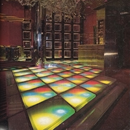

In the 1960 and 1970 decades in the United States, discothèques became an experimental ground for lighting and color installations. At this juncture, the archetypical practice of Float was revived once more for dance floors. The movie poster of the classic 1977 film "Saturday Night Fever" depicted actor John Travolta standing in an iconic posture on a colorful lit floor.

In 1978, following the release of the movie "Saturday Night Fever the previous year," the Playboy Club in Dallas added a glass lit floor to its premises. The Float installation stretched from edge-to-edge between two adjacent walls and integrated light with the architecture. The floor tiles referenced the grid pattern on the walls, and color was further integrated into each tile using lights of four different colors. The goal was to handle more architecturally the "effects appropriate to a discotheque" and to "integrate them more fully into the overall interplay of colors, shapes, and textures maintained throughout the space.9 The amorphous colored lights of the dance floor formed the center of the disco experience, comprising constant stimulation from light, music and dancing. The lit floor drew attention to the feet. The intention of Float was to remove patrons from ordinary space and time. The dramatic effects produced from up-lighting made Float apt for entertainment venues, and Float remains a feature in night clubs and bars.

In the mid-1990 decade, visual artist Piotr Uklanski emerged on the New York City art scene with his signature piece-Untitled (Dance Floor). "The sound-interactive, light-pulsating Dance Floor (1996) conjoined the formality of the modernist grid and the aesthetics of a Saturday night disco." The sculpture was activated by people's steps and their movements; in turn, people interacted with one another on the floor. "By night the floor throngs with DJs and dancers; by day, shoe scuffed and cigarette littered, it dissipates in to a wan and slightly sordid surface. Endlessly flexible, the floor has functioned in many different social contexts, including in the Museum of Modern Art in New York's Sculpture Garden, in numerous gallery spaces, in an office workers' canteen. As Uklanski observed in the MOMA exhibition catalogue, he aimed to create an object that would give and give and give but that would, at the end of the night, be unknowable, as its true nature resides in our own pleasure.'"10

After the decline of discothèques in the early 1980s, the use of large lit floors that created Float diminished once more until it remerged in the 1990 decade. In this era Float expanded beyond nightclubs and into the practice areas of boutique hotels, restaurants and retail stores. In 1995, Philippe Starck's design for the Felix restaurant in the Peninsula Hotel featured a large edge-to-edge Float installed in its "bucket-shaped" oyster bar, complemented by an internally lit onyx bar (Light Body). While visually dramatic, Float maintained the low ambient light level suitable for a bar. Starck's experiments with both lighting and translucent glass resulted in an increased brightness to achieve a uniform appearance. Consequently the floor was perceived as a single illuminated plane.

Philippe Starck applied a similar strategy for the bar of the Hudson Hotel (2001) in New York City. This time, Float encompassed a much larger area, resulting in a carpet-like floor that unified the space. This reiteration resulted in another grid in which lighted areas were crossed by darker strips to define smaller zones of light. This relatively featureless Float had a modern minimalist appeal on the floor plane that was mix-matched with a fresco-like ceiling and eclectic furniture. In this example ceiling and floor planes were topsy-turvy; the ceiling was heavy, the floor light. The floor floated; so that walking over the plane was as if walking over nothing.11

In addition to the glowing translucency seen in Starck's hospitality designs, retail examples of Float also became prevalent. In retail design lit floor experiments employed various patterns of materials and light distributions to bring texture to the floor plane. Differing light qualities were used to differentiate among various spatial zones. Float contributed to the spatial experience of moving through a store. In New York City's Final Home store (2000), a threshold formed by Float visually isolated and emphasized a core display section at the rear of the interior.

From the late 1990 to early 2000 decades, examples of Float increased in quantity and in a range of sizes and uses. Increased attention to lighting, and the improvement of lighting equipment, encouraged larger installations. Float also occasionally appeared outdoors. One of the notable examples was installed in the exterior alleyway of the Avalon nightclub (2003) designed by Desgrippes Gobe Group. Large edge-to-edge installations merged light with architecture and challenged our need for stability from the floor.

In the mid-2000s, new interactive capabilities in technology, increasingly sophisticated control systems, and a gradual adaptation of the LED technology encouraged the development of design applications of Float that changed with time or interacted with people. For example, Louis Vuitton's store in Hong Kong (2006) featured a Showcase Stair with built-in LED treads that displayed video images on walking surfaces, engaging shoppers in their visual, as well as their physical movement.12

The increased use of light as a design material led to lighting installations of Float in increasing sizes through the 2000 to 2010 decade. Bape in the Shibuya district of Tokyo (2008) constructed a multi-leveled Float with LED tiles extending from the floor up onto the walls on both sides of the entry.13 This application created a camouflage effect that effectively blurred the transition between horizontal and vertical planes. Like the nightclubs before it, however, the floor of giant pixels provided constant color changes and each color theme created a new appearance of the interior. Sometimes the changing patterns mimicked the video game Tetris in its moving shapes; at other times it displayed the store's name.

By employing the latest lighting technology, retail brands positioned themselves at the cutting-edge of interior design. Retailers integrated Float in their designs to captivate customers and to prolong their time in the stores.. Float is expanding to different practice types, including all hospitality venues, as well as residences.

end notes

- 1) Mijin Juliet Yang, "Theory Studies: Contemporary Boutique Hotel Design," (MA Thesis, Cornell University, 2005), 87-89.

- 2) Francis D. K. Ching, Inteiror Design Illustrated, 2nd ed. (Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005), 119.

- 3) Thomas Thiis-Evensen, Archetypes in Architecture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 63.

- 4) Andreas Bluhm and Louise Lippincott, Light! The Industrial Age, 1750-1900 (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2000), 34.

- 5) John Pile, A History of Interior Design, 3rd ed. (London: Laurence King Publishing Ltd. 2009), 297.

- 6) St. Charles Heritage Center, "Historic St. Charles: The Rise of Tourism and Philanthropy - Hotel Baker," St. Charles Heritage Center, http://www.stcmuseum.org/historic18.html. Accessed on 9 July 2009.

- 7) Pile, A History of Interior Design, 368.

- 8) Evelyn Jablow (1919-1997) was best known for use stainless steel frames in furniture designs, which she produced for furniture companies. Her first such collection, designed in 1962, combined steel frames with silk, velvet and fur. Among her furniture designs were a melon-shaped stainless steel serving cart and a roll-around chopping board. She was president of her own business, American Vernacular, from 1973 until her death. Its work included furniture, apparel and interior design, advertising and product development. Jablow was director of visual merchandising for Bloomingdale's from 1974 to 1976, design director of House Beautiful magazine from 1977 to 1978 and art director of L'Officiel magazine from 1982 to 1984. In 1963, she toured factories and workshops in Ireland as a consultant to the Irish Government on exports. In 1970, she was a consultant to the Wool Bureau Inc., the United States branch of the International Wool Secretariat, designing room settings using wool carpeting. She also consulted on projects in Italy, India, Japan, Portugal, Greece and France. A native of Philadelphia, she graduated from New York University in 1940. Obituary, Enid May, "Evelyn Jablow, 78, Decorator and Designer of Furniture," The New York Times (Oct. 1, 1997) http://www.nytimes.com/1997/10/01/nyregion/evelyn-jablow-78-decorator-and-a-designer-of-furniture.html; (Accessed Dec. 6, 2009).

- 9) Evidence for the use and the chronological sequence of Float as an artificial lighting archetype was developed from the following primary sources: 1970 Anonymous, "Playboy Club/Dallas," Interior Design 49, no. 6 (Jun. 1978): 124; Kate Bush / 2000 "Once Upon a Time in the East: The Art of Piotr Uklanski," Art Forum (Nov. 2002): 173; Stairs, Louis Vuitton store [2006] Peter Marino Architects; Central, Hong Kong in Anonymous, "100 Giants," Interior Design 78, no. 1 (Jan. 2007): 100; PhotoCrd: Stephane Muratet; Entry, Bape [2008] Wanderwall; Shibuya, Tokyo, Japan in Aric Chen, "The Last Days of Disco," Interior Design 79, no. 4 (Apr. 2008): 265. PhotoCrd: Jimmy Cohrssen.

bibliographic citations

1) The Interior Archetypes Research and Teaching Project, Cornell University, www.intypes.cornell.edu (accessed month & date, year).

2) Kwan, Joanne. "Theory Studies: Archetypical Artificial Lighting Practices in Contemporary Interior Design." M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2009, 143-66.