Pompidou

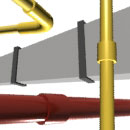

Pompidou, like its namesake building (Pompidou Center), intentionally exposes structural and mechanical systems in interior spaces. These elements are left in an original raw state, or painted, either uniformly a neutral color, or with certain ducts or pipes a bright accent color.

Pompidou | Material

application

Pompidou expresses a high tech aesthetic of exposed industrial and structural materials, such as steel, glass and aluminum, as well as mechanical systems.

research

The Great Exhibition of 1851 displayed industry's latest mechanical marvels, but of all the items exhibited the structure built to house the event received the greatest attention. The Crystal Palace designed by Joseph Paxton was a radical departure from the architecture of the period. Inspired by the structure of greenhouses, Paxton constructed the Crystal Palace out of standardized pieces of iron and glass. This is one of the earliest examples of a building constructed entirely from prefabricated parts. The skeletal structure of iron frames, columns, and girders were bolted together on the building site, and at the end of the exhibit, the building was dismantled and reassembled away from the center of London.1 This system of parts and the resulting dematerialized form has had a lasting influence on design. Describing its significance, architectural historian Richard Weston writes, "The strength of iron permitted a hitherto unprecedented lightness, and a century and a half later it remains, arguably, the most remarkable tour de force of industrialized building."2

Like the Crystal Palace, Vladmir Tatlin's proposal for a Monument to the Third International (1920) also used iron extensively. The design appeared more like a machine than a building, especially because Tatlin designed particular building components to revolve on an axis. Embracing technology and modern construction, this spiraling iron skeleton expressed the "progressive attitudes of the Revolution" symbolizing the arrival of a new society founded on new ideals.3 Although never constructed, Tatlin intended the structure to exceed the height of the Eiffel Tower, and had it been built it would have stood in stark contrast to the classical architecture prevalent in St. Petersburg.

The straightforwardness of exposed structural systems such as those occurring in buildings like railway stations and market halls satisfied the functionalist sensibilities of architects like Sigfried Giedion. In 1928, he published the influential book, Building in France, Building in Iron, Building in Ferro-Concrete. The cover designed by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy forecasted the content to follow with a bold, punctuated title, layered over an image of an impressive engineering feat: the Marseilles transport bridge. Gideon believed that through rational processes new forms of architecture would be realized which he emphatically expressed in the statement, "CONSTRUCTION BECOMES EXPRESSION. CONSTRUCTION BECOMES FORM."4

Functionalism continued to evolve alongside technology, and gained momentum in the 1970s as architects, bored with abstraction and reduction, sought new forms of expression. In Transformations in Architecture Arthur Drexler explains this ideological shift." When enthusiasm for structure is no longer satisfied with abstraction and reduction, attention shifts to details of joinery and the multiplication of parts. Thus the bones of structure may assume dinosaur proportions or joints may swell like arthritic knuckles. The opposite impulse towards structural elaboration replaces mass with line, introducing cables, pipes, and ducts. Probably the most engaging example of this overscaled hardware is the Centre National d'Art et de Culture Georges Pompidou."5

For the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, completed in 1977, architects Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano exposed a skeleton of brightly colored tubes of mechanical systems on the exterior of the building, creating a sort of street exhibition for the public. On the west side an "outer frame of lightweight horizontal and vertical struts, diagonally braced by tension-rods" resembles the scaffolding of a building under construction.6 In Interior Design in the 20th Century, authors Allan Tate and C. Ray Smith liken the tectonics to a "kind of superscale, tinker-toy decoration."7

This popularized version of Functionalism most often translates to the interior in the form of systems furniture. In the late 1960s, brothers Eberhand and Wolfgang Schnelle revolutionized corporate environments with their "office landscape" concept. As more companies adopted an open office, furniture manufactures responded with modular systems such as Bill Propst's Action Office for Herman Miller in 1968. Today these systems frequently attempt to repress their kit-of-parts nature; however, some emphasize their framework with skeletal components and exaggerated joints. Such scaffolding-like units are used not only as office furniture but also as flexible display in retail.8

end notes

- 1) John Pile, A History of Interior Design (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2005), 188.

- 2) Richard Weston, Materials, Form and Architecture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 30.

- 3) William J.R. Curtis, Modern Architecture Since 1900 (Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 1996), 201.

- 4) Weston, Materials, Form and Architecture, 79.

- 5) Arthur Drexler, Transformations in Modern Architecture (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1979), 64.

- 6) Reyner Banham, Megastructure, Urban Futures of the Recent Past (New York: Harper & Row, 1975), 214.

- 7) Allen Tate and C. Ray Smith, Interior Design in the 20th Century (New York: Harper & Row, 1986), 506.

- 8) Evidence for the archetypical use and the chronological sequence of Pompidou (originally named scaffold) as a material was developed from the following sources: 1850 Crystal Palace [1851] Joseph Paxton; London, England in John Pile, A History of Interior Design, 2nd ed. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2005), 243 / 1910 Monument to the Third International [1919] Vadmir Tatlin in William Curtis, Modern Architecture Since 1900 (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1996), 204 / 1940 Eames House [1949] Charles and Ray Eames; Pacific Palisades, CA in Andrew Weaving and Lisa Freedman, Living Modern: Bringing Modernism Home (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2002), 102; PhotoCrd: Tim Street-Porter / 1970 David and Company Hair Salon [1979] Charles Humboldt of CHD; Grand Rapids, MI in Anonymous, "Styled for Styling," Interior Design 50, no. 4 (Apr. 1979): 190; PhotoCrd: John Boucher / 1980 Burdines Galleria [1981] Raul Nunez, Walker/Group, Interior Design; Fort Lauderdale, FL in Anonymous, "The Ultimate Superstore," Interior Design 52, no. 3 (Mar. 1981): 223; PhotoCrd: Gil Amiaga; Dance Center of London Store [1985] Michael Brosche and Rex Nichols, AIA, ASID, Interior Design; London, England in Edie Lee Cohen, "Dance Gear," Interior Design 56, no. 4 (Apr. 1985): 225; PhotoCrd: Steven Brooke; Espirit Store [1986] Paul D'Urso Designs; Los Angeles, CA in "Command Performance," Architectural Record 174, no. 1 (Jan. 1986): 110-111; PhotoCrd: Timothy Hursley; Musee d'Orsay [1987] Gae Aulenti, Architect; ACT Architecture; Renovation, Gare d'Orsay, Paris-Orleans Railway Company [1900] Victor Laloux, Architect; Paris, France in Charles K. Gandee, "The Transformation of a Building," Architectural Record 175, no. 3 (Mar. 1987): 139; PhotoCrd: Serge Hambourg; Karaza Theater [1989] Tadao Ando; Tokyo, Japan in K.D. Stein, "Traveling Show," Architectural Record 177, no. 3 (Mar. 1989): 92; PhotoCrd: Richard Bryant / 1990 Zara International Store [1990] ISD; New York City in author, "Zara International," Interior Design 61, no. 15 (Nov. 1990): 168; PhotoCrd: Wolfgang Hoyt; Donna Karan Boutique [1994] Peter Marino; Jeddah, Saudi Arabia in Monica Geran, "Peter Morino," Interior Design 65, no. 11 (Sep. 1994): 139; PhotoCrd: Peter Aaron/Esto; Harriet Dorn Women's Clothing Store [1994] O'Herlihy and Warner; Santa Monica, CA in Clifford A. Pearson, "Suspended Animation," Architectural Record 182, no. 9 (Sep. 1994): 81; PhotoCrd: Greg Crawford; Gould Evans Goodman Office [1996] Gould Evans Goodman; Kansas City, MO in Edie Cohen, "Gould Evans Goldman," Interior Design 67, no. 10 (Aug. 1996): 80; PhotoCrd: Mike Sinclair; Lower East Side Films Production Co. Office [1998] Steven Harris, John Woell, Steven Roberts; New York City in Henry Urbach, "Light Construction," Interior Design 69, no. 3 (Mar. 1998): 98, 162; PhotoCrd: Scott Frances; Fanny Garbage Co. Office [1999] Specht Harpman Design; New York City in Henry Urbach, "Taking Stock," Interior Design 70, no. 4 (Mar. 1999): 140; PhotoCrd: Michael Moran / 2000 Oxygen Media Office [2000] Fernau & Hartman Architects; New York City in Clifford A. Pearson, "Fernau & Hartman Designs for Oxygen Media," Architectural Record 188, no. 9 (Sep. 2000): 89; PhotoCrd: T. Whitney Cox; Museum of the Earth [2004] Weiss/Manfredi Architects; Ithaca, NY in James S. Russell, "Weiss/Manfredi Evoked a Geology," Architectural Record 192, no. 1 (Jan. 2004): 112; PhotoCrd: Paul Warchol.

bibliographic citations

1) The Interior Archetypes Research and Teaching Project, Cornell University, www.intypes.cornell.edu (accessed month & date, year).

2) O'Brien, Elizabeth. “Material Archetypes: Contemporary Interior Design and Theory Study.” M.A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2006, 42-49.